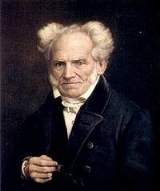

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher, best known for his work The World as Will and Representation (1819).

Unplaced by section or chapter:

not as yet placed by section or chapter:

not as yet placed by section or chapter:

Sourced

- It is the courage to make a clean breast of it in the face of every question that makes the philosopher. He must be like Sophocles' Oedipus, who, seeking enlightenment concerning his terrible fate, pursues his indefatigable inquiry even though he divines that appalling horror awaits him in the answer. But most of us carry with us the Jocasta in our hearts, who begs Oedipus, for God's sake, not to inquire further.

- Letter to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (November 1819)

- Der Mensch kann tun was er will; er kann aber nicht wollen was er will.

- Man can do what he wants but he cannot want what he wants.

- Prize Essay On The Freedom Of The Will (1839)

- Variant translations:

- Man can control what he wills, but not how he wills.

- Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot control what it is that he wants.

- Obit anus, abit onus.

- The old woman dies, the burden is lifted.

- Statement Schopenhauer wrote in Latin into his account book, after the death of a seamstress to whom he had made court-ordered payments of 15 thalers a quarter for over twenty years, after having injured her arm; as quoted in Modern Philosophy : From Descartes to Schopenhauer and Hartmann (1877) by Francis Bowen, p. 392

- The old woman dies, the burden is lifted.

- We forfeit three-fourths of ourselves in order to be like other people.

- As quoted in Dictionary of Quotations from Ancient and Modern English and Foreign Sources (1899) by James Wood, p. 624

- Compassion is the basis of all morality.

- As quoted in Thesaurus of Epigrams : A New Classified Collection of Witty Remarks, Bon Mots and Toasts (1948)

- If there is anything in the world that can really be called a man’s property, it is surely that which is the result of his mental activity.

- As quoted in Respectfully Quoted : A Dictionary of Quotations (1989).

- Change alone is eternal, perpetual, immortal.

- As quoted in Respectfully Quoted : A Dictionary of Quotations (1989); compare Heraclitus: Nothing endures but change.

The World as Will and Representation (1819; 1844)

- Quotations from translations of Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (first edition published in 1819, the second in 1844) Also translated as The World as Will and Idea - Full translation online at Wikisource

- If the reader has also received the benefit of the Vedas, the access to which by means of the Upanishads is in my eyes the greatest privilege which this still young century may claim before all previous centuries, if then the reader, I say, has received his initiation in primeval Indian wisdom, and received it with an open heart, he will be prepared in the very best way for hearing what I have to tell him. It will not sound to him strange, as to many others, much less disagreeable; for I might, if it did not sound conceited, contend that every one of the detached statements which constitute the Upanishads, may be deduced as a necessary result from the fundamental thoughts which I have to enunciate, though those deductions themselves are by no means to be found there.

- Preface to the first editon.

- How entirely does the Oupnekhat breathe throughout the holy spirit of the Vedas! How is every one who by a diligent study of its Persian Latin has become familiar with that incomparable book, stirred by that spirit to the very depth of his soul! How does every line display its firm, definite, and throughout harmonious meaning! From every sentence deep, original, and sublime thoughts arise, and the whole is pervaded by a high and holy and earnest spirit. Indian air surrounds us, and original thoughts of kindred spirits. And oh, how thoroughly is the mind here washed clean of all early en grafted Jewish superstitions, and of all philosophy that cringes before those superstitions! In the whole world there is no study, except that of the originals, so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Oupnekhat. It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death!

- On a translation of statements from the Upanishads, in the Preface to the first editon.

- Life is short and truth works far and lives long: let us speak the truth.

- Vol. I, Introduction

- The effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.

- Vol. I, Ch. II

- This art is music. It stands quite apart from all the others. In it we do not recognize the copy, the repetition, of any Idea of the inner nature of the world. Yet it is such a great and exceedingly fine art, its effect on man's innermost nature is so powerful, and it is so completely and profoundly understood by him in his innermost being as an entirely universal language, whose distinctness surpasses even that of the world of perception itself, that in it we certainly have to look for more than that exercitium arithmeticae occultum nescientis se numerare animi [exercise in arithmetic in which the mind does not know it is counting] which Leibniz took it to be.

- Vol. I, Ch. III : The World As Representation : Second Aspect, as translated by Eric F. J. Payne (1958)

- The composer reveals the innermost nature of the world, and expresses the profoundest wisdom in a language that his reasoning faculty does not understand, just as a magnetic somnambulist gives information about things of which she has no conception when she is awake. Therefore in the composer, more than in any other artist, the man is entirely separate and distinct from the artist.

- Vol. I, Ch. III, The World As Representation

- This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.

- Vol I, Ch. 4 : The World As Will : Second Aspect, § 53, as translated by Eric F. J. Payne (1958)

- Every time a man is begotten and born, the clock of human life is wound up anew to repeat once more its same old tune that has already been played innumerable times, movement by movement and measure by measure, with insignificant variations.

- Vol. I, Ch. 4 : The World As Will : Second Aspect, as translated by Eric F. J. Payne (1958) p. 322

- There is only one inborn erroneous notion ... that we exist in order to be happy ... So long as we persist in this inborn error ... the world seems to us full of contradictions. For at every step, in great things and small, we are bound to experience that the world and life are certainly not arranged for the purpose of maintaining a happy existence ... hence the countenances of almost all elderly persons wear the expression of ... disappointment.

- Vol II "On the Road to Salvation"

- Life is a business that does not cover the costs.

- Vol II "On the Vanity and Suffering of Life"

- At the age of five years to enter a spinning-cotton or other factory, and from that time forth to sit there daily, first ten, then twelve, and ultimately fourteen hours, performing the same mechanical labour, is to purchase dearly the satisfaction of drawing breath. But this is the fate of millions, and that of millions more is analogous to it.

- Vol II : "On the Vanity and Suffering of Life", as translated by R. B. Haldane, and J. Kemp in The World as Will and Idea (1886), p. 389

Unplaced by section or chapter:

- Cited as from Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, but without further information as to volume or chapter.

- Jedes Kind ist gewissermaßen ein Genie; und jedes Genie ist gewissermassen ein Kind.

- Every child is in a way a genius; and every genius is in a way a child.

- ...this our world, which is so real, with all its suns and milky ways is--nothing.

- Whoever heard me assert that the grey cat playing just now in the yard is the same one that did jumps and tricks there five hundred years ago will think whatever he likes of me, but it is a stranger form of madness to imagine that the present-day cat is fundamentally an entirely different one.

- Quoted by Jorge Luis Borges in his essay "A History of Eternity"

- In early youth, as we contemplate our coming life, we are like children in a theatre before the curtain is raised, sitting there in high spirits and eagerly waiting for the play to begin.

Parerga and Paralipomena (1851)

- Various portions of this large work have been translated and published in English under various titles. It is here divided up into sections corresponding to those of the original volumes and some of the cited translations.

- Philosophy ... is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions.

- Vol I

Aphorisms on the Wisdom of Life

- Quotes from Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit, using various translations, also translated as On The Wisdom of Life : Aphorisms

- Honor has not to be won; it must only not be lost.

- Vol. 1. Ch. 4

- Pride is an established conviction of one’s own paramount worth in some particular respect, while vanity is the desire of rousing such a conviction in others, and it is generally accompanied by the secret hope of ultimately coming to the same conviction oneself. Pride works from within; it is the direct appreciation of oneself. Vanity is the desire to arrive at this appreciation indirectly, from without.

- Vol. 1, Ch. 4, § 2

- Rascals are always sociable — more’s the pity! and the chief sign that a man has any nobility in his character is the little pleasure he takes in others’ company.

- Vol. 1, Ch. 5, § 9

not as yet placed by section or chapter:

- cited as from Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit, Aphorisms on the Wisdom of Life or "The Wisdom of Life" but without further information; some of the quotes in this section are of the original German phrase, with only improvised English translation, addition of published English translations is welcomed.

- Childish and altogether ludicrous is what you yourself are and all philosophers; and if a grown-up man like me spends fifteen minutes with fools of this kind, it is merely a way of passing the time. I've now got more important things to do. Goodbye!

- "Thrasymachus", in "On the Indestructibility of our Essential Being by Death, in Essays and Aphorisms (1970) as translated by R. J. Hollingdale, p. 76

- A reproach can only hurt if it hits the mark. Whoever knows that he does not deserve a reproach can treat it with contempt.

- The brain may be regarded as a kind of parasite of the organism, a pensioner, as it were, who dwells with the body.

- National character is only another name for the particular form which the littleness, perversity and baseness of mankind take in every country. Every nation mocks at other nations, and all are right.

- Variant translation: Every nation criticizes every other one — and they are all correct.

- As quoted by Wolfgang Pauli in a letter to Abraham Pais (17 August 1950) published in The Genius of Science (2000) by Abraham Pais, p. 242

- Variant translation: Every nation criticizes every other one — and they are all correct.

- Honor ... means that a man is not exceptional; fame, that he is. Fame is something which must be won; honor, only something which must not be lost.

- Variant translation: Fame is something which must be won; honor is something which must not be lost.

- Im allgemeinen freilich haben die Weisen aller Zeiten immer dasselbe gesagt, und die Toren, d.h. die unermessliche Majorität aller Zeiten, haben immer dasselbe, nämlich das Gegenteil getan; und so wird es denn auch ferner bleiben.

- In general admittedly the Wise of all times have always said the same thing, and the fools, that is to say the vast majority of all times, have always done the same thing, i.e. the opposite; and so it will remain in the future.

-

- Die Gegenwart eines Gedankens ist wie die Gegenwart einer Geliebten.

- The presence of a thought is like the presence of a lover.

- Die Erinnerung wirkt wie das Sammlungsglas in der Camera obscura: Sie zieht alles zusammen und bringt dadurch ein viel schöneres Bild hervor, als sein Original ist.

- The memory works like the collection glass in the Camera obscura: It gathers all together from it is produced a far more beautiful picture, than was originally there.

- Alles, alles kann einer vergessen, nur nicht sich selbst, sein eigenes Wesen.

- One can forget everything, everything, only not oneself, one's own being.

- Zu unserer Besserung bedürfen wir eines Spiegels.

- For our improvement we need a mirror.

- Meistens belehrt uns erst der Verlust über den Wert der Dinge.

- Mostly it is loss which teaches us about the worth of things.

- Die wohlfeilste Art des Stolzes hingegen ist der Nationalstolz. Denn er verrät in dem damit Behafteten den Mangel an individuellen Eigenschaften, auf die er stolz sein könnte, indem er sonst nicht zu dem greifen würde, was er mit so vielen Millionen teilt. Wer bedeutende persönliche Vorzüge besitzt, wird vielmehr die Fehler seiner eigenen Nation, da er sie beständig vor Augen hat, am deutlichsten erkennen. Aber jeder erbärmliche Tropf, der nichts in der Welt hat, darauf er stolz sein könnte, ergreift das letzte Mittel, auf die Nation, der er gerade angehört, stolz zu sein. Hieran erholt er sich und ist nun dankbarlich bereit, alle Fehler und Torheiten, die ihr eigen sind, mit Händen und Füßen zu verteidigen.

- The cheapest form of pride however is national pride. For it betrays in the one thus afflicted the lack of individual qualities of which he could be proud, while he would not otherwise reach for what he shares with so many millions. He who possesses significant personal merits will rather recognise the defects of his own nation, as he has them constantly before his eyes, most clearly. But that poor beggar who has nothing in the world of which he can be proud, latches onto the last means of being proud, the nation to which he belongs to. Thus he recovers and is now in gratitude ready to defend with hands and feet all errors and follies which are its own.

- Kap. II

- The cheapest form of pride however is national pride. For it betrays in the one thus afflicted the lack of individual qualities of which he could be proud, while he would not otherwise reach for what he shares with so many millions. He who possesses significant personal merits will rather recognise the defects of his own nation, as he has them constantly before his eyes, most clearly. But that poor beggar who has nothing in the world of which he can be proud, latches onto the last means of being proud, the nation to which he belongs to. Thus he recovers and is now in gratitude ready to defend with hands and feet all errors and follies which are its own.

- Je weniger einer, in Folge objektiver oder subjektiver Bedingungen, nötig hat, mit den Menschen in Berührung zu kommen, desto besser ist er daran.

- The less one, as a result of objective or subjective conditions, has to come into contact with people, the better off one is for it.

- Was nun andrerseits die Menschen gesellig macht, ist ihre Unfähigkeit, die Einsamkeit und in dieser sich selbst zu ertragen.

- What now on the other hand makes people sociable is their incapacity to endure solitude and thus themselves.

Counsels and Maxims

- Counsels and Maxims, as translated by T. Bailey Saunders (also on Wikisource: Counsels and Maxims).

- The fundament upon which all our knowledge and learning rests is the inexplicable.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 1, § 1

- Do not shorten the morning by getting up late, or waste it in unworthy occupations or in talk; look upon it as the quintessence of life, as to a certain extent sacred. Evening is like old age: we are languid, talkative, silly. Each day is a little life: every waking and rising a little birth, every fresh morning a little youth, every going to rest and sleep a little death.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 2 : Our Relation To Ourselves

- All the cruelty and torment of which the world is full is in fact merely the necessary result of the totality of the forms under which the will to live is objectified.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 14, § 164

- The discovery of truth is prevented more effectively, not by the false appearance things present and which mislead into error, not directly by weakness of the reasoning powers, but by preconceived opinion, by prejudice.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 1, § 17

- How very paltry and limited the normal human intellect is, and how little lucidity there is in the human consciousness, may be judged from the fact that, despite the ephemeral brevity of human life, the uncertainty of our existence and the countless enigmas which press upon us from all sides, everyone does not continually and ceaselessly philosophize, but that only the rarest of exceptions do.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 3, § 39

- Suicide may also be regarded as an experiment — a question which man puts to Nature, trying to force her to answer. The question is this: What change will death produce in a man’s existence and in his insight into the nature of things? It is a clumsy experiment to make; for it involves the destruction of the very consciousness which puts the question and awaits the answer.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 13, § 160

- Newspapers are the second hand of history. This hand, however, is usually not only of inferior metal to the other hands, it also seldom works properly.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 19, § 233

- Great minds are related to the brief span of time during which they live as great buildings are to a little square in which they stand: you cannot see them in all their magnitude because you are standing too close to them.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 20, § 242

- Patriotism, when it wants to make itself felt in the domain of learning, is a dirty fellow who should be thrown out of doors.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 21, § 255

- As the biggest library if it is in disorder is not as useful as a small but well-arranged one, so you may accumulate a vast amount of knowledge but it will be of far less value to you than a much smaller amount if you have not thought it over for yourself; because only through ordering what you know by comparing every truth with every other truth can you take complete possession of your knowledge and get it into your power. You can think about only what you know, so you ought to learn something; on the other hand, you can know only what you have thought about.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 22, § 257 "On Thinking for Yourself" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms(1970) as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Variant translation: Just as the largest library, badly arranged, is not so useful as a very moderate one that is well arranged, so the greatest amount of knowledge, if not elaborated by our own thoughts, is worth much less than a far smaller volume that has been abundantly and repeatedly thought over.

- Truth that has been merely learned is like an

artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose; at best,

like a nose made out of another's flesh; it adheres to

us only ‘because it is put on. But truth acquired by

thinking of our own is like a natural limb; it alone

really belongs to us. This is the fundamental difference

between the thinker and the mere man of learning.

The intellectual attainments of a man who thinks

for himself resemble a fine painting, where the light

and shade are correct, the tone sustained, the colour

perfectly harmonised; it is true to life. On the other

hand, the intellectual attainments of the mere man of

learning are like a large palette, full of all sorts of

colours, which at most are systematically arranged,

but devoid of harmony, connection and meaning.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 22, § 261

- Reading is merely a surrogate for thinking for yourself; it means letting someone else direct your thoughts. Many books, moreover, serve merely to show how many ways there are of being wrong, and how far astray you yourself would go if you followed their guidance. You should read only when your own thoughts dry up, which will of course happen frequently enough even to the best heads; but to banish your own thoughts so as to take up a book is a sin against the holy ghost; it is like deserting untrammeled nature to look at a herbarium or engravings of landscapes.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 22, § 261

- Variant translations:

- Reading is thinking with some one else's head

instead of one's own.

- As translated by T. Bailey Saunders

- Reading is equivalent to thinking with someone else’s head instead of with one’s own.

- Buying books would be a good thing if one could also buy the time to read them in: but as a rule the purchase of books is mistaken for the appropriation of their contents.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 23, § 296a

- * Hatred is a thing of the heart, contempt a thing of the head. Hatred and contempt are decidedly antagonistic towards one another and mutually exclusive. A great deal of hatred, indeed, has no other source than a compelled respect for the superior qualities of some other person; conversely, if you were to consider hating every miserable wretch you met you would have your work cut out: it is much easier to despise them one and all. True, genuine contempt, which is the obverse of true, genuine pride, stays hidden away in secret and lets no one suspect its existence: for if you let a person you despise notice the fact, you thereby reveal a certain respect for him, inasmuch as you want him to know how low you rate him — which betrays not contempt but hatred, which excludes contempt and only affects it. Genuine contempt, on the other hand, is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 24, § 324

- Variant translation: Hatred is an affair of the heart; contempt that of the head.

- As translated by Eric F. J. Payne

- The word of man is the most durable of all material.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 25, sect. 298

- Every parting gives a foretaste of death, every reunion a hint of the resurrection.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 26, § 310, as translated by Eric F. J. Payne

- We can come to look upon the deaths of our enemies with as much regret as we feel for those of our friends, namely, when we miss their existence as witnesses to our success.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 26, sect. 311a

- Money is human happiness in the abstract: he, then, who is no longer capable of enjoying human happiness in the concrete devotes his heart entirely to money.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 26, § 320

- Obstinacy is the result of the will forcing itself into the place of the intellect.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 26, § 321

- Only a male intellect clouded by the sexual drive could call the stunted, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped and short-legged sex the fair sex.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 27, § 369 (18

- In our monogamous part of the world, to marry means to halve one’s rights and double one’s duties.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 27, § 370

- Variant translation: To marry is to halve your rights and double your duties.

- A man’s face as a rule says more, and more interesting things, than his mouth, for it is a compendium of everything his mouth will ever say, in that it is the monogram of all this man’s thoughts and aspirations.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 29, § 377

- That the outer man is a picture of the inner, and the face an expression and revelation of the whole character, is a presumption likely enough in itself, and therefore a safe one to go on; borne out as it is by the fact that people are always anxious to see anyone who has made himself famous .... Photography ... offers the most complete satisfaction of our curiosity.

- Vol. 2, Ch. 29, § 377

- As the strata of the earth preserve in succession the living creatures of past epochs, so the shelves of libraries preserve in succession the errors of the past and their expositions, which like the former were very lively and made a great commotion in their own age but now stand petrified and stiff in a place where only the literary palaeontologist regards them.

- Vol. 2 "On Books and Writing" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Two Chinamen visiting Europe went to the theatre for the first time. One of them occupied himself with trying to understand the theatrical machinery, which he succeeded in doing. The other, despite his ignorance of the language, sought to unravel the meaning of the play. The former is like the astronomer, the latter the philosopher.

- Vol. 2 "On Various Subjects" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- The animals are much more content with mere existence than we are; the plants are wholly so; and man is so according to how dull and insensitive he is. The animal’s life consequently contains less suffering but also less pleasure than the human’s, the direct reason being that on the one hand it is free from care and anxiety and the torments that attend them, but on the other is without hope and therefore has no share in that anticipation of a happy future which, together with the enchanting products of the imagination which accompany it, is the source of most of our greatest joys and pleasures. The animal lacks both anxiety and hope because its consciousness is restricted to what is clearly evident and thus to the present moment: the animal is the present incarnate.

- Vol. 2 "On the Suffering of the World" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Talent works for money and fame; the motive which moves genius to productivity is, on the other hand, less easy to determine. It isn’t money, for genius seldom gets any. It isn’t fame: fame is too uncertain and, more closely considered, of too little worth. Nor is it strictly for its own pleasure, for the great exertion involved almost outweighs the pleasure. It is rather an instinct of a unique sort by virtue of which the individual possessed of genius is impelled to express what he has seen and felt in enduring works without being conscious of any further motivation. It takes place, by and large, with the same sort of necessity as a tree brings forth fruit, and demands of the world no more than a soil on which the individual can flourish.

- Vol. 2 "On Philosophy and the Intellect" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- The poet presents the imagination with images from life and human characters and situations, sets them all in motion and leaves it to the beholder to let these images take his thoughts as far as his mental powers will permit. This is why he is able to engage men of the most differing capabilities, indeed fools and sages together. The philosopher, on the other hand, presents not life itself but the finished thoughts which he has abstracted from it and then demands that the reader should think precisely as, and precisely as far as, he himself thinks. That is why his public is so small.

- Vol. 2 "On Philosophy and the Intellect" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Opinion is like a pendulum and obeys the same law. If it goes past the centre of gravity on one side, it must go a like distance on the other; and it is only after a certain time that it finds the true point at which it can remain at rest.

- Vol. 2 "Further Psychological Observations" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Men are by nature merely indifferent to one another; but women are by nature enemies.

- Vol. 2 "On Women" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- Writers may be classified as meteors, planets, and fixed stars. A meteor makes a striking effect for a moment. You look up and cry “There!” and it is gone forever. Planets and wandering stars last a much longer time. They often outshine the fixed stars and are confounded by them by the inexperienced; but this only because they are near. It is not long before they must yield their place; nay, the light they give is reflected only, and the sphere of their influence is confined to their orbit — their contemporaries. Their path is one of change and movement, and with the circuit of a few years their tale is told. Fixed stars are the only ones that are constant; their position in the firmament is secure; they shine with a light of their own; their effect today is the same as it was yesterday, because, having no parallax, their appearance does not alter with a difference in our standpoint. They belong not to one system, one nation only, but to the universe. And just because they are so very far away, it is usually many years before their light is visible to the inhabitants of this earth.

- Vol. 2 "The Art of Literature" as translated in Essays and Aphorisms (1970), as translated by R. J. Hollingdale

- For an author to write as he speaks is just as reprehensible as the opposite fault, to speak as he writes; for this gives a pedantic effect to what he says, and at the same time makes him hardly intelligible.

- The Art of Literature

not as yet placed by section or chapter:

- cited as from Counsels and Maxims but without further information

- A man of intellect is like an artist who gives a concert without any help from anyone else, playing on a single instrument — a piano, say, which is a little orchestra in itself. Such a man is a little world in himself; and the effect produced by various instruments together, he produces single-handed, in the unity of his own consciousness. Like the piano, he has no place in a symphony; he is a soloist and performs by himself — in soli tude, it may be; or if in the company with other instruments, only as principal; or for setting the tone, as in singing.

- In youth it is the outward aspect of things that most engages us; while in age, thought or reflection is the predominating quality of the mind. Hence, youth is the time for poetry, and age is more inclined to philosophy. In practical affairs it is the same: a man shapes his resolutions in youth more by the impression that the outward world makes upon him; whereas, when he is old, it is thought that determines his actions.

- There is no doubt that life is given us, not to be enjoyed, but to be overcome — to be got over.

Studies in Pessimism

- Full text online at Wikisource

- A quick test of the assertion that enjoyment outweighs pain in this world, or that they are at any rate balanced, would be to compare the feelings of an animal engaged in eating another with those of the animal being eaten

- "On the Sufferings of the World"

- Hatred comes from the heart; contempt from the head; and neither feeling is quite within our control.

- "Psychological Observations"

- Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.

- "Psychological Observations"

- Every parting gives a foretaste of death; every coming together again a foretaste of the resurrection.

- "Psychological Observations"

- Dissimulation is innate in woman, and almost as much a quality of the stupid as of the clever.

- "Of Women"

- There are 80,000 prostitutes in London alone and what are they, if not bloody sacrifices on the altar of monogamy?

- "Of Women"

- Noise is the most impertinent of all forms of interruption. It is not only an interruption, but also a disruption of thought.

- "On Noise"

On Books and Reading

On Books and Reading- The heavy armor becomes the light dress of childhood; the pain is brief, the joy unending.

- Original:

- Der schwere Panzer wird zum Flügelkleide

- Kurz ist der Schmerz, unendlich ist die Freude.

- Literally:

- The heavy armor becomes the winged dress

- brief is the pain, unending is the joy.

not yet placed by volume, chapter or section

- Quotes cited as from Parerga and Paralipomena, but without further translation or section information.

- Because people have no thoughts to deal in, they deal cards, and try and win one another’s money. Idiots!

- Nature shows that with the growth of intelligence comes increased capacity for pain, and it is only with the highest degree of intelligence that suffering reaches its supreme point.

- Footnote, unspecified section.

Essays

- Quotes sourced to various essays, not yet sourced to the original German volumes.

- The two foes of human happiness are pain and boredom.

- Personality; or, What a Man Is

- A man who has no mental needs, because his intellect is of the narrow and normal amount, is, in the strict sense of the word, what is called a philistine.

- Personality; or, What a Man Is

- Intellect is invisible to the man who has none.

- Our Relation to Others, § 23

- There is no more mistaken path to happiness than worldliness, revelry, high life.

- Our Relation to Others, § 24

- To free a man from error is to give, not to take away. Knowledge that a thing is false is a truth. Error always does harm; sooner or later it will bring mischief to the man who harbors it. Then give up deceiving people; confess ignorance of what you don't know, and leave everyone to form his own articles of faith for himself. Perhaps they won't turn out so bad, especially as they'll rub one another's corners down, and mutually rectify mistakes. The existence of many views will at any rate lay a foundation of tolerance. Those who possess knowledge and capacity may betake themselves to the study of philosophy, or even in their own persons carry the history of philosophy a step further.

- "Religion : A Dialogue."

- Variant translation: To free a man from error does not mean to take something from him, but to give him something.

- Men of learning are those who have read the contents of books. Thinkers, geniuses, and those who have enlightened the world and furthered the race of men, are those who have made direct use of the book of the world.

- Truth that has been merely learned is like an artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose; at best, like a nose made out of another's flesh; it adheres to us only ‘because it is put on. But truth acquired by thinking of our own is like a natural limb; it alone really belongs to us. This is the fundamental difference between the thinker and the mere man of learning. The intellectual attainments of a man who thinks for himself resemble a fine painting, where the light and shade are correct, the tone sustained, the colour perfectly harmonised; it is true to life. On the other hand, the intellectual attainments of the mere man of learning are like a large palette, full of all sorts of colours, which at most are systematically arranged, but devoid of harmony, connection and meaning.

- In the sphere of thought, absurdity and perversity remain the masters of the world, and their dominion is suspended only for brief periods.

- "The Art of Controversy" as translated by T. Bailey Saunders

- In Christian ethics ... animals are seen as mere things. They can therefore be used for vivisection, hunting, coarsing, bull-fights and horse-races and can be whipped to death as they struggle along with their heavy carts of stone. Shame on such a morality that fails to recognise the eternal essence that exists in every living thing and shines forth with inscrutable significance from all eyes that see the sun.

- On the Basis of Morality

- The chief objection that I have to Pantheism is that it says nothing. To call the world "God" is not to explain it; it is only to enrich our language with a superfluous synonym for the word "world".

- On Pantheism as quoted in Faiths of Famous Men in Their Own Words (1900) by John Kenyon Kilbourn; also in Religion : A Dialogue and Other Essays (2007), p. 40

- Jede menschliche Vollkommenheit ist einem Fehler verwandt, in welchen überzugehn sie droht.

- Every human perfection is linked to an error which it threatens to turn into.

- Zur Ethik

- Alles Wollen entspringt aus Bedürfnis, also aus Mangel, also aus Leiden.

- All wanting comes from need, therefore from lack, therefore from suffering.

- Welt und Mensch II, S. 230ff

- All wanting comes from need, therefore from lack, therefore from suffering.

- Es gibt nur eine Heilkraft, und das ist die Natur; in Salben und Pillen steckt keine. Höchstens können sie der Heilkraft der Natur einen Wink geben, wo etwas für sie zu tun ist.

- There is only one healing force, and that is nature; in pills and ointments there is none. At most they can give the healing force of nature a hint about where there is something for it to do.

- Neue Paralipomena

- There is only one healing force, and that is nature; in pills and ointments there is none. At most they can give the healing force of nature a hint about where there is something for it to do.

On Authorship and Style

- "On Authorship and Style" as translated by Mrs. Rudolf Dircks

- On Authorship and On Style translated by T. B. Saunders on Wikisource.

- There are, first of all, two kinds of authors: those who write for the subject’s sake, and those who write for writing’s sake. The first kind have had thoughts or experiences which seem to them worth communicating, while the second kind need money and consequently write for money.

- No greater mistake can be made than to imagine that what has been written latest is always the more correct; that what is written later on is an improvement on what was written previously; and that every change means progress. Men who think and have correct judgment, and people who treat their subject earnestly, are all exceptions only. Vermin is the rule everywhere in the world: it is always at hand and busily engaged in trying to improve in its own way upon the mature deliberations of the thinkers.

- A book can never be anything more than the impression of its author’s thoughts. The value of these thoughts lies either in the matter about which he has thought, or in the form in which he develops his matter — that is to say, what he has thought about it.

- For a work to become immortal it must possess so many excellences that it will not be easy to find a man who understands and values them all; so that there will be in all ages men who recognise and appreciate some of these excellences; by this means the credit of the work will be retained throughout the long course of centuries and ever-changing interests, for, as it is appreciated first in this sense, then in that, the interest is never exhausted.

- The little honesty that exists among authors is discernible in the unconscionable way they misquote from the writings of others.

- Truth that is naked is the most beautiful, and the simpler its expression the deeper is the impression it makes; this is partly because it gets unobstructed hold of the hearer’s mind without his being distracted by secondary thoughts, and partly because he feels that here he is not being corrupted or deceived by the arts of rhetoric, but that the whole effect is got from the thing itself.

- The law of simplicity and naïveté applies to all fine art, for it is compatible with what is most sublime.

True brevity of expression consists in a man only saying what is worth saying, while avoiding all diffuse explanations of things which every one can think out for himself; that is, it consists in his correctly distinguishing between what is necessary and what is superfluous. On the other hand, one should never sacrifice clearness, to say nothing of grammar, for the sake of being brief. To impoverish the expression of a thought, or to obscure or spoil the meaning of a period for the sake of using fewer words shows a lamentable want of judgment.

Disputed

- All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.

- As cited in Truth : Resuming the Age of Reason (2006) by Mahlon Marr; the earliest attribution of this to Schopenhauer yet found dates to around 1986; it is also sometimes misattributed to George Bernard Shaw, and a similar statement is often attributed to Mahatma Gandhi: "First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win."

- Variant : Every truth passes through three stages before it is recognized. In the first it is ridiculed, in the second it is opposed, in the third it is regarded as self- evident.

- The earliest similar statements yet found in published works online are:

- It has been said that the reception of an original contribution to knowledge may be divided into three phases: during the first it is ridiculed as not true, impossible or useless; during the second, people say that there may be something in it but it would never be of any practical use; and in the third and final phase, when the discovery has received general recognition, there are usually people who say that it is not original and has been anticipated by others. [a note at the bottom of the page adds: This saying seems to have originated from Sir James Mackenzie (The Beloved Physician, by R. M. Wilson, John Murray, London)]

- William Ian Beardmore Beveridge, in The Art of Scientific Investigation (1955), p. 113

- First, it is ridiculed; second, it is subject to argument: third, it is accepted.

- Earl B. Morgan, in "The Accident Prevention Problem in the Small Shop" in Safety Engineering Vol. 33 (1950), p. 366

- The four stages of acceptance: 1. This is worthless nonsense. 2. This is an interesting, but perverse, point of view. 3. This is true, but quite unimportant. 4. I always said so.

- J. B. S. Haldane, Journal of Genetics 1963 (Vol 58, p.464) in a review of 'The Truth About Death'.

Quotes about Schopenhauer

- Ich glaube nicht an die Freiheit des Willens. Schopenhauers Wort: »Der Mensch kann wohl tun was er will, aber er kann nicht wollen, was er will.« begleitet mich in allen Lebenslagen und versöhnt mich mit den Handlungen der Menschen, auch wenn sie mir recht schmerzlich sind. Diese Erkenntnis von der Unfreiheit des Willens schützt mich davor, mich selbst und die Mitmenschen als handelnde und urteilende Individuen allzu ernst zu nehmen und den guten Humor zu verlieren.

- I do not believe in freedom of will. Schopenhauer's words, "Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot want what he wants", accompany me in all life situations and console me in my dealings with people, even those that are really painful to me. This recognition of the unfreedom of the will protects me from taking myself and my fellow men too seriously as acting and judging individuals and losing good humour.

- Albert Einstein in Mein Glaubensbekenntnis (August 1932)

- I do not believe in freedom of will. Schopenhauer's words, "Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot want what he wants", accompany me in all life situations and console me in my dealings with people, even those that are really painful to me. This recognition of the unfreedom of the will protects me from taking myself and my fellow men too seriously as acting and judging individuals and losing good humour.

- Kant and Berkeley always seemed to be very deep thinkers, but, with Schopenhauer, you seem to be looking at the bottom straight away.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein

- He speaks to me as no other philosopher does, direct and in his own human voice, a fellow spirit, a pentratingly perceptive friend, with a hand on my elbow and a twinkle in his eye.

- Bryan Magee

- When I met Borges some time ago and remarked that I was about to embark on writing a book about Schopenhauer, he became excited and started talked volubly about how much Schopenhauer had meant to him. It was the desire to read Schopenhauer in the original, he said, that had made him learn German; and when people asked him, which they often had, why he with his love of intricate structure had never attempted a systematic exposition of the world-view which underlay his writings, his reply was that he did not do it because it had already been done by Schopenhauer."

- Bryan Magee, The Philosophy of Schopenhauer, pg. 389

- ...impassioned, lucid Schopenhauer...

- Jorge Luis Borges, from his essay "A History of Eternity"

- We are struck by the psychological force and even fierceness with which he reveals the deepest recesses of the human heart.

- Eric F. J. Payne, in his introduction to his 1958 translation of The World as Will and Representation

- He was the first to speak of the suffering of the world, which visibly and glaringly surrounds us, and of confusion, passion, evil — all those things which the [other philosophers] hardly seemed to notice and always tried to resolve into all-embracing harmony and comprehensiblility. Here at last was a philosopher who had the courage to see that all was not for the best in the fundaments of the universe.

- Carl Jung, in Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1961), p. 69

- ...fourmish her in Spinner's housery at the earthbest schoppinhour...

- James Joyce