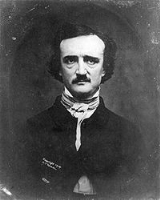

Edgar Allan Poe

Sourced

- A dark unfathom'd tide

Of interminable pride —

A mystery, and a dream,

Should my early life seem.- "Imitation", Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827)

- O, human love! thou spirit given,

On Earth, of all we hope in Heaven!- "Tamerlane", l. 177 (1827)

- The happiest day — the happiest hour

My sear'd and blighted heart hath known,

The highest hope of pride and power,

I feel hath flown.- "The Happiest Day", st. 1 (1827)

- Sound loves to revel in a summer night.

- Al Aaraaf (1829).

- Years of love have been forgot

In the hatred of a minute.- To M——— (1829), reported in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 10th ed. (1919).

- From childhood's hour I have not been

As others were — I have not seen

As others saw — I could not bring

My passions from a common spring —

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow — I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone —

And all I lov'd — I lov'd alone —- "Alone", l. 1-8 (written 1829, published 1875)

- And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view.- "Alone", l. 20-22

- Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood,

The Elfin from the green grass, and from me

The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?- "Sonnet. To Science", l. 12-14 (1829)

- It is with literature as with law or empire — an established name is an estate in tenure, or a throne in possession.

- "Letter to Mr. B — ", preface to Poems (1831)

- Music, when combined with a pleasurable idea, is poetry; music without the idea is simply music; the idea without the music is prose from its very definitiveness.

- "Letter to Mr. B — "

- Helen, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicean barks of yore,

That gently, o'er a perfumed sea,

The weary, wayworn wanderer bore

To his own native shore.On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home

To the glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.- "To Helen", st. 1-2 (1831)

- If I could dwell

Where Israfel

Hath dwelt, and he where I,

He might not sing so wildly well

A mortal melody,

While a bolder note than this might swell

From my lyre within the sky.- "Israfel", st. 8 (1831)

- Come! let the burial rite be read — the funeral song be sung! —

An anthem for the queenliest dead that ever died so young —

A dirge for her the doubly dead in that she died so young.- "Lenore", st. 1 (1831)

- Vastness! and Age! and Memories of Eld!

Silence! and Desolation! and dim Night!

I feel ye now — I feel ye in your strength.- "The Coliseum", st. 2 (1833)

- Thou wast all that to me, love,

For which my soul did pine —

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine.- "To One In Paradise", st. 1 (1834)

- And all my days are trances,

And all my nightly dreams

Are where thy dark eye glances,

And where thy footstep gleams —

In what ethereal dances,

By what eternal streams.- "To One In Paradise", st. 4

- Convinced myself, I seek not to convince.

- "Berenice" (1835)

- But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, out of joy is sorrow born. Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, or the agonies which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been.

- "Berenice"

- There is then no analogy whatever between the operations of the Chess-Player, and those of the calculating machine of Mr. Babbage, and if we choose to call the former a pure machine we must be prepared to admit that it is, beyond all comparison, the most wonderful of the inventions of mankind.

- Poe stating his arguments that Maelzel's Chess-Player was a hoax. Maelzel's Chess-Player, Southern Literary Journal (April 1836)

- During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country, and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher.

- "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839)

- In the greenest of our valleys

By good angels tenanted,

Once a fair and stately palace —

Radiant palace — reared its head.- "The Haunted Palace" (1839), st. 1

- This—all this—was in the olden

Time long ago.- "The Haunted Palace" (1839), st. 2

- While, like a ghastly rapid river,

Through the pale door

A hideous throng rush out forever

And laugh — but smile no more.- "The Haunted Palace" (1839), st. 5

- Few persons can be made to believe that it is not quite an easy thing to invent a method of secret writing which shall baffle investigation. Yet it may be roundly asserted that human ingenuity cannot concoct a cipher which human ingenuity cannot resolve.

- "A Few Words on Secret Writing" in Graham's Magazine (July 1841)

- They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.

- "Eleonora" (1841)

- Had the routine of our life at this place been known to the world, we should have been regarded as madmen —; although, perhaps, as madmen of a harmless nature.

- "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

- "The best chess-player in Christendom may be little more than the best player of chess; but proficiency in whist implies capacity for success in all these more important undertakings where mind struggles with mind."

- "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

- To observe attentively is to remember distinctly.

- "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

- And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

- "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842)

- While the angels, all pallid and wan,

Uprising, unveiling, affirm

That the play is the tragedy, "Man",

And its hero the Conqueror Worm.- "The Conqueror Worm" (1843), st. 5

- Man is an animal that diddles, and there is no animal that diddles but man.

- "Diddling: Considered As One Of The Exact Sciences"; first published as "Raising the Wind" in Saturday Courier (1843-10-14)

- The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?

- "The Premature Burial" (1844)

- By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule —

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE — out of TIME.- "Dreamland", st. 1 (1845)

- With me poetry has been not a purpose, but a passion; and the passions should be held in reverence: they must not — they cannot at will be excited, with an eye to the paltry compensations, or the more paltry commendations, of mankind.

- The Raven and Other Poems (1845), Preface

- Thou wouldst be loved? — then let thy heart

From its present pathway part not!

Being everything which now thou art,

Be nothing which thou art not.

So with the world thy gentle ways,

Thy grace, thy more than beauty,

Shall be an endless theme of praise,

And love — a simple duty.- "To Frances S. Osgood" (1845)

- The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could; but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge. You, who so well know the nature of my soul, will not suppose, however, that I gave utterance to a threat. At length I would be avenged; this was a point definitely settled — but the very definitiveness with which it was resolved precluded the idea of risk. I must not only punish, but punish with impunity. A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.

- "The Cask of Amontillado" (1846)

- For the love of God Montressor!

- "The Cask of Amontillado" (1846)

- Beauty is the sole legitimate province of the poem.

- "The Philosophy of Composition" (published 1846)

- The death then of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover.

- "The Philosophy of Composition" (published 1846)

- The object, Truth, or the satisfaction of the intellect, and the object, Passion, or the excitement of the heart, are, although attainable, to a certain extent, in poetry, far more readily attainable in prose.

- The Philosophy of Composition (published 1846).

- Can it be fancied that Deity ever vindictively

Made in his image a mannikin merely to madden it?- "The Rationale of Verse", III (1848). Compare: ""What! out of senseless Nothing to provoke / A conscious Something to resent the yoke", FitzGerald, Omar Khayyám.

- There is no oath which seems to me so sacred as that sworn by the all-divine love I bear you. — By this love, then, and by the God who reigns in Heaven, I swear to you that my soul is incapable of dishonor — that, with the exception of occasional follies and excesses which I bitterly lament, but to which I have been driven by intolerable sorrow, and which are hourly committed by others without attracting any notice whatever — I can call to mind no act of my life which would bring a blush to my cheek — or to yours. If I have erred at all, in this regard, it has been on the side of what the world would call a Quixotic sense of the honorable — of the chivalrous.

- "Letter to Mrs. Whitman" (1848-10-18)

- Depend upon it, after all, Thomas, Literature is the most noble of professions. In fact, it is about the only one fit for a man. For my own part, there is no seducing me from the path.

- "Letter to Frederick W. Thomas" (1849-02-14)

- Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.- "Eldorado", st. 1 (1849)

- "Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,"

The shade replied, —

"If you seek for Eldorado!"- "Eldorado", st. 4

- You are not wrong, who deem

That my days have been a dream;

Yet if hope has flown away

In a night, or in a day,

In a vision, or in none,

Is it therefore the less gone?

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.- "A Dream Within a Dream" (1849)

- O God! Can I not save

One from the pitiless wave?

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?- "A Dream Within A Dream" (1849)

- Thank Heaven! the crisis —

The danger is past,

And the lingering illness

Is over at last —

And the fever called "Living"

Is conquered at last.- "For Annie", st. 1 (1849)

- Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells.- "The Bells", st. 1 (1849)

- Hear the mellow wedding bells

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight!- "The Bells", st. 2 (1849)

- As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester — and this is my last jest.

- "Hop-Frog" (1850)

- I attacked with great resolution the editorial matter, and, reading it from beginning to end without understanding a syllable, conceived the possibility of its being Chinese, and so re-read it from the end to the beginning, but with no more satisfactory result.

- "The Angel of the Odd — An Extravaganza" (1850)

- These fellows, knowing the extravagant gullibility of the age, set their wits to work in the imagination of improbable possibilities — of odd accidents, as they term them; but to a reflecting intellect (like mine," I added, in parenthesis, putting my forefinger unconsciously to the side of my nose,) "to a contemplative understanding such as I myself possess, it seems evident at once that the marvelous increase of late in these 'odd accidents' is by far the oddest accident of all. For my own part, I intend to believe nothing henceforward that has anything of the 'singular' about it.

- "The Angel Of The Odd: An Extravaganza"

The City in the Sea (1831)

- Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.- St. 1

- So blend the turrets and shadows there

That all seem pendulous in air,

While from a proud tower in the town

Death looks gigantically down.- St. 2

- And when, amid no earthly moans,

Down, down that town shall settle hence,

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones,

Shall do it reverence.- St. 5

The Tell-Tale Heart (1843)

- TRUE! — nervous — very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?

- Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture — a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees — very gradually — I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye for ever.

- If you still think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

- "Villains!" I shrieked, "dissemble no more! I admit the deed! — tear up the planks! — here, here! — it is the beating of his hideous heart!"

The Black Cat (1843)

- For the most wild, yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief. Mad indeed would I be to expect it, in a case where my very senses reject their own evidence. Yet, mad am I not — and very surely do I not dream. But to-morrow I die, and to-day I would unburthen my soul.

- There is something in the unselfish and self-sacrificing love of a brute, which goes directly to the heart of him who has had frequent occasion to test the paltry friendship and gossamer fidelity of mere Man.

- I grew, day by day, more moody, more irritable, more regardless of the feelings of others. I suffered myself to use intemperate language to my wife. At length, I even offered her personal violence.

- One night, returning home, much intoxicated, from one of my haunts about town, I fancied that the cat avoided my presence. I seized him; when, in his fright at my violence, he inflicted a slight wound upon my hand with his teeth. The fury of a demon instantly possessed me. I knew myself no longer. My original soul seemed, at once, to take its flight from my body; and a more than fiendish malevolence, gin-nurtured, thrilled every fiber of my frame. I took from my waistcoat-pocket a penknife, opened it, grasped the poor beast by the throat, and deliberately cut one of its eyes from the socket!

- Yet I am not more sure that my soul lives, than I am that perverseness is one of the primitive impulses of the human heart — one of the indivisible primary faculties, or sentiments, which give direction to the character of man. Who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or a stupid action, for no other reason than because he knows he should not? Have we not a perpetual inclination, in the teeth of our best judgement, to violate that which is Law, merely because we understand it to be such?

- Beneath the pressure of torments such as these, the feeble remnant of the good within me succumbed. Evil thoughts became my sole intimates — the darkest and most evil of thoughts. The moodiness of my usual temper increased to hatred of all things and of all mankind; while, from the sudden, frequent, and ungovernable outbursts of a fury to which I now blindly abandoned myself, my uncomplaining wife, alas! was the most usual and the most patient of sufferers.

- It is impossible to describe, or to imagine, the deep, the blissful sense of relief which the absence of the detested creature occasioned in my bosom. It did not make its appearance during the night — and thus for one night at least, since its introduction into the house, I soundly and tranquilly slept; aye, slept even with the burden of murder upon my soul!

- For one instant the party upon the stairs remained motionless, through extremity of terror and of awe. In the next, a dozen stout arms were toiling at the wall. It fell bodily. The corpse, already greatly decayed and clotted with gore, stood erect before the eyes of the spectators. Upon its head, with red extended mouth and solitary eye of fire, sat the hideous beast whose craft had seduced me into murder, and whose informing voice had consigned me to the hangman. I had walled the monster up within the tomb!

Marginalia (November 1844)

First published in the Democratic Review- If you wish to forget anything on the spot, make a note that this thing is to be remembered.

- After reading all that has been written, and after thinking all that can be thought on the topics of God and the soul, the man who has a right to say that he thinks at all, will find himself face to face with the conclusion that, on these topics, the most profound thought is that which can be the least easily distinguished from the most superficial sentiment.

- A strong argument for the religion of Christ is this — that offences against Charity are about the only ones which men on their death-beds can be made, not to understand, but to feel, as crime.

- If any ambitious man have a fancy to revolutionize at one effort the universal world of human thought, human opinion, and human sentiment, the opportunity is his own — the road to immortal renown lies straight, open, and unencumbered before him. All that he has to do is to write and publish a very little book. Its title should be simple — a few plain words — "My Heart Laid Bare." But — this little book must be true to its title.

- How many good books suffer neglect through the inefficiency of their beginnings!

- In reading some books we occupy ourselves chiefly with the thoughts of the author; in perusing others, exclusively with our own.

- I have sometimes amused myself by endeavouring to fancy what would be the fate of an individual gifted, or rather accursed, with an intellect very far superior to that of his race. Of course he would be conscious of his superiority; nor could he (if otherwise constituted as man is) help manifesting his consciousness. Thus he would make himself enemies at all points. And since his opinions and speculations would widely differ from those of all mankind — that he would be considered a madman is evident. How horribly painful such a condition! Hell could invent no greater torture than that of being charged with abnormal weakness on account of being abnormally strong.

In like manner, nothing can be clearer than that a very generous spirit — truly feeling what all merely profess — must inevitably find itself misconceived in every direction — its motives misinterpreted. Just as extremeness of intelligence would be thought fatuity, so excess of chivalry could not fail of being looked upon as meanness in the last degree — and so on with other virtues. This subject is a painful one indeed. That individuals have so soared above the plane of their race is scarcely to be questioned; but, in looking back through history for traces of their existence, we should pass over all the biographies of the "good and the great," while we search carefully the slight records of wretches who died in prison, in Bedlam, or upon the gallows.

- Were I called on to define, very briefly, the term "Art," I should call it "the reproduction of what the Senses perceive in Nature through the veil of the soul." The mere imitation, however accurate, of what is in Nature, entitles no man to the sacred name of "Artist."

- I have great faith in fools — self-confidence my friends will call it.

- That man is not truly brave who is afraid either to seem or to be, when it suits him, a coward.

The Raven (1844)

- Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.- Stanza 1.

- Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.- Stanza 2.

- Sorrow for the lost Lenore —

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore —

Nameless here for evermore.- Stanza 2.

- And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before.- Stanza 3.

- Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.- Stanza 5.

- Perched upon a bust of Pallas, just above my chamber door,—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.- Stanza 7.

- "Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore —

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."- Stanza 8.

- "Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore.- Stanza 11.

- "Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil!"

- Stanza 15.

- "Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! — quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."- Stanza 17.

- And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door.- Stanza 18.

- And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted — nevermore!- Stanza 18.

Ulalume (1847)

- The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crisped and sere —

The leaves they were withering and sere;

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year.- St. 1

- Here once, through an alley Titanic,

Of cypress, I roamed with my Soul —

Of cypress, with Psyche, my Soul.- St. 2

- Thus I pacified Psyche and kissed her,

And tempted her out of her gloom.- St. 8

Annabel Lee (1849)

- It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee; —

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.- St. 1

- I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love —

I and my Annabel Lee —

With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.- St. 2

- But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we —

Of many far wiser than we —

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee- St. 5

- In her sepulcher there by the sea —

In her tomb by the sounding sea.- St. 6

The Poetic Principle (1850)

- Published 1850-08-31

- I hold that a long poem does not exist. I maintain that the phrase, "a long poem," is simply a flat contradiction in terms.

I need scarcely observe that a poem deserves its title only inasmuch as it excites, by elevating the soul. The value of the poem is in the ratio of this elevating excitement. But all excitements are, through a psychal necessity, transient. That degree of excitement which would entitle a poem to be so called at all, cannot be sustained throughout a composition of any great length.

- There neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified — more supremely noble than this very poem — this poem per se — this poem which is a poem and nothing more — this poem written solely for the poem's sake.

- I would define, in brief, the Poetry of words as the Rhythmical Creation of Beauty. Its sole arbiter is taste. With the intellect or with the conscience, it has only collateral relations. Unless incidentally, it has no concern whatever either with duty or with truth.

Quotes about Poe

- He was an adventurer into the vaults and cellars and horrible underground passages of the human soul. He sounded the horror and the warning of his own doom.

- D.H. Lawrence in Studies in Classic American Literature (1924)

- There comes Poe, with his Raven, like Barnaby Rudge,

Three-fifths of him genius, and two-fifths sheer fudge.- James Russell Lowell in A Fable for Critics (1848)

- Poe is a kind of Hawthorne and delirium tremens.

- Leslie Stephen in Hours in a Library (1874)

- Poe...was perhaps the first great nonstop literary drinker of the American nineteenth century. He made the indulgences of Coleridge and De Quincy seem like a bit of mischief in the kitchen with the cooking sherry.

- James Thurber in Alarms and Diversions (1957)