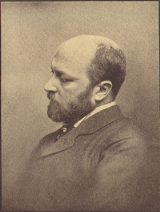

Henry James

Henry James, OM brother of the philosopher and psychologist William James, was an American-born author and literary critic of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- See also: The American Scene

Sourced

- In the long run an opinion often borrows credit from the forbearance of its patrons.

- "Essays in Criticism by Matthew Arnold," North American Review (July 1865)

- Everything about Florence seems to be coloured with a mild violet, like diluted wine.

- Letter to Henry James Sr. (26 October 1869)

- The face of nature and civilization in this our country is to a certain point a very sufficient literary field. But it will yield its secrets only to a really grasping imagination... To write well and worthily of American things one need even more than elsewhere to be a master.

- Letter to Charles Eliot Norton (1871-01-16)

- It's a complex fate, being an American, and one of the responsibilities it entails is fighting against a superstitious valuation of Europe.

- Letter to Charles Eliot Norton (1872-02-04)

- Deep experience is never peaceful.

- de Mauves, Galaxy Magazine (February/March 1874), ch. V, reprinted in A Passionate Pilgrim (1875) and later in The Madonna of the Future and Other Tales (1879) and the New York Edition of James' works, vol. 13 (1908)

- True happiness, we are told, consists in getting out of one's self; but the point is not only to get out — you must stay out; and to stay out you must have some absorbing errand.

- Roderick Hudson (1875), ch. I: Rowland

- It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature.

- Hawthorne, (1879) ch. I: The Early Years

- One might enumerate the items of high civilization, as it exists in other countries, which are absent from the texture of American life, until it should become a wonder to know what was left.

- Hawthorne, ch. II: Early Manhood

- Whatever question there may be of his [Thoreau's] talent, there can be none, I think, of his genius. It was a slim and crooked one; but it was eminently personal. He was imperfect, unfinished, inartistic; he was worse than provincial — he was parochial; it is only at his best that he is readable.

- Hawthorne, ch. IV: Brook Farm and Concord

- He would agree that life is a little worth living — or worth living a little; but would remark that, unfortunately, to live little enough, we have to live a great deal.

- Hawthorne, ch. V: The Three American Novels

- It is, I think, an indisputable fact that Americans are, as Americans, the most self-conscious people in the world, and the most addicted to the belief that the other nations of the earth are in a conspiracy to undervalue them.

- Hawthorne, ch. VI: England and Italy

- Cats and monkeys — monkeys and cats — all human life is there!

- The Madonna of the Future (1879)

- My choice is the old world — my choice, my need, my life.

- Notebook entry, Boston, 1881-11-25

- Don't mind anything anyone tells you about anyone else. Judge everyone and everything for yourself.

- The Portrait of a Lady (1881), ch. XXIII

- The real offence, as she ultimately perceived, was her having a mind of her own at all. Her mind was to be his — attached to his own like a small garden-plot to a deer-park.

- The Portrait of a Lady (1881), ch. XLII

- You wanted to look at life for yourself — but you were not allowed; you were punished for your wish. You were ground in the very mill of the conventional!

- The Portrait of a Lady, ch. LIV

- Young men of this class never do anything for themselves that they can get other people to do for them, and it is the infatuation, the devotion, the superstition of others that keeps them going. These others in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred are women.

- Washington Square (1881), ch. XIV

- She ordered a cup of tea, which proved excessively bad, and this gave her a sense that she was suffering in a romantic cause.

- Washington Square, ch. XV

- I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme.

- "Venice," The Century Magazine, vol. XXV (November 1882), reprinted in Portraits of Places (1883) and later in Italian Hours (1909), ch: I: Venice, pt. I

- Though there are some disagreeable things in Venice there is nothing so disagreeable as the visitors.

- "Venice," The Century Magazine, vol. XXV (November 1882), reprinted in Portraits of Places (1883) and later in Italian Hours (1909), ch. I: Venice, pt. II

- There are two kinds of taste in the appreciation of imaginative literature: the taste for emotions of surprise and the taste for emotions of recognition.

- "Anthony Trollope," Century Magazine (July 1883); reprinted in Partial Portraits (1888)

- A tradition is kept alive only by something being added to it.

- "Robert Louis Stevenson," Century Magazine (April 1888)

- If the artist is necessarily sensitive, does that sensitiveness form in its essence a state constantly liable to shade off into the morbid? Does this liability, moreover, increase in proportion as the effort is great and the ambition intense?

- "The Journal of the Brothers de Goncourt," Fortnightly Review (October 1888)

- To take what there is, and use it, without waiting forever in vain for the preconceived — to dig deep into the actual and get something out of that — this doubtless is the right way to live.

- Notebook entry, London, 1889-05-12

- The superiority of one man's opinion over another's is never so great as when the opinion is about a woman.

- The Tragic Muse (1890), ch. IX

- The practice of "reviewing"... in general has nothing in common with the art of criticism.

- Criticism (1893)

- The critical sense is so far from frequent that it is absolutely rare, and the possession of the cluster of qualities that minister to it is one of the highest distinctions... In this light one sees the critic as the real helper of the artist, a torchbearing outrider, the interpreter, the brother... Just in proportion as he is sentient and restless, just in proportion as he reacts and reciprocates and penetrates, is the critic a valuable instrument.

- Criticism

- However incumbent it may be on most of us to do our duty, there is, in spite of a thousand narrow dogmatisms, nothing in the world that anyone is under the least obligation to like — not even (one braces one's self to risk the declaration) a particular kind of writing.

- Flaubert (1893)

- We work in the dark — we do what we can — we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.

- The Middle Years (1893)

- She had an unequalled gift, especially pen in hand, of squeezing big mistakes into small opportunities.

- "Greville Fane", from The Real Thing: and Other Tales (1893)

- The only success worth one's powder was success in the line of one's idiosyncrasy. Consistency was in itself distinction, and what was talent but the art of being completely whatever it was that one happened to be?

- "The Next Time," The Yellow Book, vol. VI (July 1895)

- The time-honored bread-sauce of the happy ending.

- Theatricals: Second Series (1895)

- Vereker’s secret, my dear man — the general intention of his books: the string the pearls were strung on, the buried treasure, the figure in the carpet.

- The Figure in the Carpet (1896)

- He is outside of everything, and an alien everywhere. He is an aesthetic solitary. His beautiful, light imagination is the wing that on the autumn evening just brushes the dusky window.

- "Nathaniel Hawthorne" in Library of the World's Best Literature, vol. XII (1897), ed. Charles Dudley Warner

- People talk about the conscience, but it seems to me one must just bring it up to a certain point and leave it there. You can let your conscience alone if you're nice to the second housemaid.

- Said by Mrs. Brookenham in The Awkward Age (1899), book VI, ch. III

- Live all you can — it's a mistake not to. It doesn't so much matter what you do in particular, so long as you have your life. If you haven't had that, what have you had?... What one loses one loses; make no mistake about that...The right time is any time that one is still so lucky as to have.... Live!

- The Ambassadors (1903), book V, ch. II

- She was a woman who, between courses, could be graceful with her elbows on the table.

- The Ambassadors, book VII, ch. I

- I'm glad you like adverbs — I adore them; they are the only qualifications I really much respect.

- Letter to Miss M. Betham Edwards (1912-01-05)

- We must know, as much as possible, in our beautiful art...what we are talking about — and the only way to know is to have lived and loved and cursed and floundered and enjoyed and suffered. I think I don't regret a single "excess" of my responsive youth — I only regret, in my chilled age, certain occasions and possibilities I didn't embrace.

- Letter to Hugh Walpole (1913-08-21)

- I still, in presence of life... have reactions — as many as possible... It's, I suppose, because I am that queer monster, the artist, an obstinate finality, an inexhaustible sensibility. Hence the reactions — appearances, memories, many things, go on playing upon it with consequences that I note and "enjoy" (grim word!) noting. It all takes doing — and I do. I believe I shall do yet again — it is still an act of life.

- Letter to Henry Adams (1914-03-21)

- The effect, if not the prime office, of criticism is to make our absorption and our enjoyment of the things that feed the mind as aware of itself as possible, since that awareness quickens the mental demand, which thus in turn wanders further and further for pasture. This action on the part of the mind practically amounts to a reaching out for the reasons of its interest, as only by its ascertaining them can the interest grow more various. This is the very education of our imaginative life.

- The New Novel (1914)

- It is art that makes life, makes interest, makes importance, for our consideration and application of these things, and I know of no substitute whatever for the force and beauty of its process.

- Letter to H.G. Wells (1915-07-10)

- The full, the monstrous demonstration that Tennyson was not Tennysonian.

- The Middle Years (1917), ch. VI

- If I were to live my life over again, I would be an American. I would steep myself in America, I would know no other land.

- Said to Hamlin Garland in 1906 and quoted by Garland in Roadside Meetings (1930; reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1-417-90788-6), ch. XXXVI: Henry James at Rye (p. 461)

- Summer afternoon — summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language.

- Quoted by Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (1934), ch. 10

- So here it is at last, the distinguished thing!

- After suffering a stroke (1915-12-02), the first of several which led to his death, as recounted by Edith Wharton in A Backward Glance (1934), ch. 14: "He is said to have told his old friend Lady Prothero, when she saw him after the first stroke, that in the very act of falling (he was dressing at the time) he heard in the room a voice which was distinctly, it seemed, not his own, saying: 'So here it is at last, the distinguished thing!'"

- Three things in human life are important. The first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.

- Said to his nephew, Willie James, in 1902; quoted in Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, vol V: The Master 1901-1916 (1972)

The Art of Fiction (1884)

Originally published in Longman's Magazine (1884-09-04) and reprinted in Partial Portraits (1888)- The only reason for the existence of a novel is that it does attempt to represent life.

- Variant text: The only reason for the existence of a novel is that it does compete with life.

- The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting.

- The advantage, the luxury, as well as the torment and responsibility of the novelist, is that there is no limit to what he may attempt as an executant — no limit to his possible experiments, efforts, discoveries, successes.

- Experience is never limited, and it is never complete; it is an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness and catching every air-borne particle in its tissue.

- The power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern, the condition of feeling life, in general, so completely that you are well on your way to knowing any particular corner of it — this cluster of gifts may almost be said to constitute experience, and they occur in country and in town, and in the most differing stages of education. If experience consists of impressions, it may be said that impressions are experience, just as (have we not seen it?) they are the very air we breathe. Therefore, if I should certainly say to a novice, "Write from experience, and experience only," I should feel that this was a rather tantalizing monition if I were not careful immediately to add, "Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!"

- What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the illustration of character?

- We must grant the artist his subject, his idea, what the French call his donnée; our criticism is applied only to what he makes of it. Naturally I do not mean that we are bound to like it or find it interesting: in case we do not our course is perfectly simple — to let it alone. We may believe that of a certain idea even the most sincere novelist can make nothing at all, and the event may perfectly justify our belief; but the failure will have been a failure to execute, and it is in the execution that the fatal weakness is recorded. If we pretend to respect the artist at all we must allow him his freedom of choice, in the face, in particular cases, of innumerable presumptions that the choice will not fructify. Art derives a considerable part of its beneficial exercise from flying in the face of presumptions, and some of the most interesting experiments of which it is capable are hidden in the bosom of common things.

- There are few things more exciting to me, in short, than a psychological reason.

The Turn of the Screw (1898)

- The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be.

- Introduction

- It was as if, at moments, we were perpetually coming into sight of subjects before which we must stop short, turning suddenly out of alleys that we perceived to be blind, closing with a little bang that made us look at each other — for, like all bangs, it was something louder than we had intended— the doors we had indiscreetly opened.

- Ch. XIII

- The place, with its gray sky and withered garlands, its bared spaces and scattered dead leaves, was like a theater after the performance — all strewn with crumpled playbills.

- Ch. XIII

- I caught him, yes, I held him — it may be imagined with what a passion; but at the end of a minute I began to feel what it truly was that I held. We were alone with the quiet day, and his little heart, dispossessed, had stopped.

- Ch. XXIV

Prefaces (1907-1909)

- Really, universally, relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so.

- Roderick Hudson

- There is, I think, no more nutritive or suggestive truth... than that of the perfect dependence of the "moral" sense of a work of art on the amount of felt life concerned in producing it. The question comes back thus, obviously, to the kind and the degree of the artist's prime sensibility, which is the soil out of which his subject springs.

- The Portrait of a Lady

- To see deep difficulty braved is at any time, for the really addicted artist, to feel almost even as a pang the beautiful incentive, and to feel it verily in such sort as to wish the danger intensified. The difficulty most worth tackling can only be for him, in these conditions, the greatest the case permits of.

- The Portrait of a Lady

- Life being all inclusion and confusion, and art being all discrimination and selection, the latter, in search of the hard latent value with which it alone is concerned, sniffs round the mass as instinctively and unerringly as a dog suspicious of some buried bone.

- The Spoils of Poynton

- The fatal futility of Fact.

- The Spoils of Poynton

- No themes are so human as those that reflect for us, out of the confusion of life, the close connection of bliss and bale, of the things that help with the things that hurt, so dangling before us forever that bright hard medal, of so strange an alloy, one face of which is somebody's right and ease and the other somebody's pain and wrong.

- What Maisie Knew

- The effort really to see and really to represent is no idle business in face of the constant force that makes for muddlement. The great thing is indeed that the muddled state too is one of the very sharpest of the realities, that it also has color and form and character, has often in fact a broad and rich comicality.

- What Maisie Knew

- To criticize is to appreciate, to appropriate, to take intellectual possession, to establish in fine a relation with the criticized thing and to make it one's own.

- What Maisie Knew

- The historian, essentially, wants more documents than he can really use; the dramatist only wants more liberties than he can really take.

- The Aspern Papers; The Turn of the Screw; The Liar; The Two Faces

- We are divided of course between liking to feel the past strange and liking to feel it familiar.

- The Aspern Papers; The Turn of the Screw; The Liar; The Two Faces

- The ever importunate murmur, "Dramatize it, dramatize it!"

- The Altar of the Dead

- In art economy is always beauty.

- The Altar of the Dead

- The terrible fluidity of self-revelation.

- The Ambassadors

Misattributed

- Be not afraid of life. Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help create the fact.

- William James, "Is Life Worth Living?," The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897)

- Ideas are, in truth, force.

- "Ideas are, in truth, forces. Infinite, too, is the power of personality. A union of the two always makes history." - Henry James (1879-1947), Charles W. Eliot (1930), 2 vol. This namesake was James' nephew, the son of William James. His life of Eliot earned him the 1931 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

- Life's too short for chess.

- Henry James Byron, Our Boys (1875), Act I