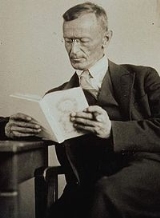

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. In 1946, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. His best known works include Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Glass Bead Game (also known as Magister Ludi) all of which explore an individual's search for spirituality.

Sourced

Peter Camenzind (1904)

- In the beginning was the myth. God, in his search for self-expression, invested the souls of Hindus, Greeks, and Germans with poetic shapes and continues to invest each child's soul with poetry every day.

- Variant translation: In the beginning was the myth. Just as the great god composed and struggled for expression in the souls of the Indians, the Greeks and Germanic peoples, so to it continues to compose daily in the soul of every child.

- Oh, love isn't there to make us happy. I believe it exists to show us how much we can endure.

- That's the way it is when you love. It makes you suffer, and I have suffered much in the years since. But it matters little that you suffer, so long as you feel alive with a sense of the close bond that connects all living things, so long as love does not die!

Gertrude (1910)

- As translated by Hilda Rosner

- When I take a long look at my life, as though from outside, it does not appear particularly happy. Yet I am even less justified in calling it unhappy, despite all its mistakes. After all, it is foolish to keep probing for happiness or unhappiness, for it seems to me it would be hard to exchange the unhappiest days of my life for all the happy ones. If what matters in a person's existence is to accept the inevitable consciously, to taste the good and bad to the full and to make for oneself a more individual, unaccidental and inward destiny alongside one's external fate, then my life has been neither empty nor worthless. Even if, as it is decreed by the gods, fate has inexorably trod over my external existence as it does with everyone, my inner life has been of my own making . I deserve its sweetness and bitterness and accept full responsibility for it.

- I was given the freedom to discover my own inclination and talents, to fashion my inmost pleasures and sorrows myself and to regard the future not as an alien higher power but as the hope and product of my own strength.

- At about the age of six or seven, I realized that of all the invisible powers the one I was destined to be most strongly affected and dominated by was music. From that moment on I had a world of my own, a sanctuary and a heaven that no one could take away from me. Oh, music! A melody occurs to you; you sing it silently, inwardly only; you steep your being in it;it takes possession of all your strength and emotions, and during the time it lives in you, it effaces all that is fortuitous, evil, coarse and sad in you; it brings the world into harmony with you, it makes burdens light and gives wings to to depressed spirits.

- That is where my dearest and brightest dreams have ranged — to hear for the duration of a heartbeat the universe and the totality of life in its mysterious, innate harmony.

- Was that really love? I saw all these passionate people reel about and drift haphazardly as if driven by a storm, the man filled with desire today, satiated on the morrow, loving fiercely and discarding brutally, sure of no affection and happy in no love...

- Young people have many pleasures and many sorrows, because they only have themselves to think of, so every wish and every notion assume importance; every pleasure is tasted to the full, but also every sorrow, and many who find that their wishes cannot be fulfilled, immediately put an end to their lives.

- That life is difficult, I have often bitterly realized. I now had further cause for serious reflection. Right up to the present I have never lost the feeling of contradiction that lies behind all knowledge. My life has been miserable and difficult, and yet to others, and sometimes to myself, it has seemed rich and wonderful. Man's life seems to me like a long, weary night that would be intolerable if there were not occasionally flashes of light, the sudden brightness of which is so comforting and wonderful, that the moments of their appearance cancel out and justify the years of darkness.

- If a man does not think too much, he rejoices at rising in the morning, and at eating and drinking. He finds satisfaction in them and does not want them to be otherwise. But if he ceases to take things for granted, he seeks eagerly and hopefully during the course of the day for moments of real life, the radiance of which makes him rejoice and obliterates the awareness of time and all thoughts on the meaning and purpose of everything. One can call these moments creative, because they seem to give a feeling of union with the creator, and while they last, one is sensible of everything being necessary, even what is seemingly fortuitous. It is what the mystics call union with God. Perhaps it is the excessive radiance of these moments that make everything else appear so dark. Perhaps it is the feeling of liberation, the enchanting lightness and the suspended bliss that make the rest of life seem so difficult, demanding and oppressive. I do not know. I have not travelled very far in thought and philosophy. However I do know that if there is a state of bliss and a paradise, it must be an uninterrupted sequence of such moments, and if this state of bliss can be attained through suffering and dwelling in pain, then no sorrow or pain can be so great that one should attempt to escape from it.

- The south winds roars at night,

Curlews hasten in their flight,

The air is damp and warm.

Desire to sleep has vanished now,

Spring has arrived in the night

In the wake of a storm.

- Be still, my heart, away with pain!

Though passion stirs again

In blood that now flows slowly

And leads to paths once known,

These paths you tread in vain

For youth has flown.

- Passion is always a mystery and unaccountable, and unfortunately there is no doubt that life does not spare its purest children and often it is just the most deserving people who cannot help loving those that destroy them.

- I found some consolation or narcotic. Sometimes it was a woman, sometimes a good friend — yes, you too once helped me that way — at other times it was music or applause in the theater. But now these things no longer give me pleasure and that is why I drink. I could never sing without first having a couple of drinks, but now I can also not think, talk, live and feel tolerably well without first having a couple of drinks.

- It was no different with my own life, and with Gertrude's and that of many others. Fate was not kind, life was capricious and terrible, and there was no good or reason in nature. But there is good and reason in us, in human beings, with whom fortune plays, and we can be stronger than nature and fate, if only for a few hours. And we can draw close to one another in times of need, understand and love one another, and live to comfort each other. And sometimes, when the black depths are silent, we can do even more. We can then be gods for moments, stretch out a commanding hand and create things which were not there before and which, when they are created, continue to live without us. Out of sounds, words, and other frail and worthless things, we can construct playthings — songs and poems full of meaning, consolation and goodness, more beautiful and enduring than the grim sport of fortune and destiny. We can keep the spirit of God in our hearts and, at times, when we are full of Him, He can appear in our eyes and our words, and also talk to others who do no know or do not wish to know Him. We cannot evade life's course, but we can school ourselves to be superior to fortune and also to look unflinchingly upon the most painful things.

Demian (1919)

- Demian: The Story of Emil Sinclair's Youth (1919), first published under the pseudonym "Emil Sinclair"

- I cannot tell my story without reaching a long way back.

- Prologue

- Novelists when they write novels tend to take an almost godlike attitude toward their subject, pretending to a total comprehension of the story, a man's life, which they can therefore recount as God Himself might, nothing standing between them and the naked truth, the entire story meaningful in every detail. I am as little able to do this as the novelist is, even though my story is more important to me than any novelist's is to him — for this is my story; it is the story of a man, not of an invented, or possible, or idealized, or otherwise absent figure, but of a unique being of flesh and blood. Yet, what a real living human being is made of seems to be less understood today than at any time before, and men — each one of whom represents a unique and valuable experiment on the part of nature — are therefore shot wholesale nowadays. If we were not something more than unique human beings, if each one of us could really be done away with once and for all by a single bullet, story telling would lose all purpose. But every man is more than just himself; he also represents the unique, the very special and always significant and remarkable point at which the world's phenomena intersect, only once in this way and never again. That is why every man's story is important, eternal, sacred; that is why every man, as long as he lives and fulfills the will of nature, is wondrous, and worthy of every consideration. In each individual the spirit has become flesh, in each man the creation suffers, within each one a redeemer is nailed to the cross.

Few people nowadays know what man is. Many sense this ignorance and die the more easily because of it, the same way that I will die more easily once I have completed this story.- Prologue

- I do not consider myself less ignorant than most people. I have been and still am a seeker, but I have ceased to question stars and books; I have begun to listen to the teachings my blood whispers to me. My story is not a pleasant one; it is neither sweet nor harmonious, as invented stories are; it has the taste of nonsense and chaos, of madness and dreams — like the lives of all men who stop deceiving themselves.

Each man's life represents the road toward himself, and attempt at such a road, the intimation of a path. No man has ever been entirely and completely himself. Yet each one strives to become that — one in an awkward, the other in a more intelligent way, each as best he can.- Prologue

- We all have a common origin, the Mothers, we all come out of the same abyss; but each of us, a trial throw of the dice from the depths, strives toward his own goal. We can understand one another, but each of us can only interpret himself.

- Prologue

- Variant translation: We all share the same origin, our mothers; all of us come in at the same door. But each of us — experiments of the depths — strives toward his own destiny. We can understand one another, but each of us is able to interpret himself to himself alone.

- People with courage and character always seem sinister to the rest. It was a scandal that a breed of fearless and sinister people ran around freely, so they attached a nickname and a myth to these people to get even with them, to make up for the many times they had felt afraid.

- I realize today that nothing in the world is more distasteful to a man than to take the path that leads to himself.

- Then came those years in which I was forced to recognize the existence of a drive within me that had to make itself small and hide from the world of light. The slowly awakening sense of my own sexuality overcame me, as it does every person, like an enemy and terrorist, as something forbidden, tempting, and sinful. What my curiosity sought, what dreams, lust and fear created — the great secret of puberty — did not fit at all into my sheltered childhood. I behaved like everyone else. I led the double life of a child who is no longer a child. My conscious self lived within the familiar and sanctioned world; it denied the new world that dawned within me. Side by side with this I lived in a world of dreams, drives and desires of a chthonic nature, across which my conscious self desperately built its fragile bridges, for the childhood world within me was falling apart. Like most parents, mine were no help with the new problems of puberty, to which no reference was ever made. All they did was take endless trouble in supporting my hopeless attempts to deny reality and to continue dwelling in a childhood world that was becoming more and more unreal. I have no idea whether parents can be of help, and I do not blame mine. It was my own affair to come to terms with myself and to find my own way, and like most well-brought-up children, I managed it badly.

- Only the ideas that we actually live are of any value. You knew all along that your sanctioned world was only half the world and you tried to suppress the second half the same way the priests and teachers do. You won't succeed. No one succeeds in this once he has begun to think.

- Certainly you shouldn't go kill somebody or rape a girl, no! But you haven't reached the point where you can understand the actual meaning of "permitted" and "forbidden." You've only sensed part of the truth. You will feel the other part, too, you can depend on it. For instance, for about a year you have had to struggle with a drive that is stronger than any other and which is considered "forbidden." The Greeks and many other peoples, on the other hand, elevated this drive, made it divine and celebrated it in great feasts. What is forbidden, in other words, is not something eternal; it can change. Anyone can sleep with a woman as soon as he's been to a pastor with her and has married her, yet other races do it differently, even nowadays. Each of us has to find out for himself what is permitted and what is forbidden — forbidden for him. It's possible for one never to transgress a single law and still be a bastard. And vice versa. Actually it's only a question of convenience. Those who are too lazy and comfortable to think for themselves and be their own judges obey the laws. Others sense their own laws within them; things are forbidden to them that every honorable man will do any day in the year and other things are allowed to them that are generally despised. Each person must stand on his own feet.

- Now everything changed. My childhood world was breaking apart around me. My parents eyed me with a certain embarrassment. My sisters had become strangers to me. A disenchantment falsified and blunted my usual feelings and joys: the garden lacked fragrance, the woods held no attraction for me, the world stood around me like a clearance sale of last year's secondhand goods, insipid, all its charm gone. Books were so much paper, music a grating noise. That is the way leaves fall around a tree in autumn, a tree unaware of the rain running down its sides, of the sun or the frost, and of life gradually retreating inward. The tree does not die. It waits.

- One of the aphorisms occurred to me now and I wrote it under the picture: "Fate and temperament are two words for one and the same concept." That was clear to me now.

- The bird fights its way out of the egg. The egg is the world. Who would be born must first destroy a world. The bird flies to God. The God's name is Abraxas.

- Variant translation: The bird is struggling out of the egg. The egg is the world. Whoever wants to be born must first destroy a world. The bird is flying to God. The name of the God is called Abraxas.

- As translated by W. J. Strachan

- Variant translation: The bird is struggling out of the egg. The egg is the world. Whoever wants to be born must first destroy a world. The bird is flying to God. The name of the God is called Abraxas.

- We ought not to consider the opinions of those sects as naïve as they appear from the rationalist point of view. Science as we know it today was unknown to antiquity. Instead there existed a preoccupation with philosophical and mystical truths which was highly developed. What grew out of this preoccupation was to some extent merely pedestrian magic and frivolity; perhaps it frequently led to deceptions and crimes, but this magic, too, had noble antecedents in a profound philosophy. As, for instance, the teachings concerning Abraxas which I cited a moment ago. This name occurs in connection with Greek magical formulas and is frequently considered to be the name of some magician's helper such as certain uncivilized tribes believe in even at present. But it appears that Abraxas has much deeper significance. We may conceive of the name as that of the godhead whose symbolic task is the uniting of godly and devilish elements.

- Abraxas was the god who was both god and devil.

- I had grown a thin mustache, I was a full-grown man, and yet I was completely helpless and without a goal in life.

- I wanted only to try to live in accord with the promptings which came from my true self. Why was that so very difficult?

- Our god's name is Abraxas and he is God and Satan and he contains both the luminous and the dark world. Abraxas does not take exception to any of your thoughts, any of your dreams. Never forget that. But he will leave you once you've become blameless and normal. Then he will leave you and look for a different vessel in which to brew his thoughts.

- If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of yourself. What isn't part of ourselves doesn't disturb us.

- I live in my dreams — that's what you sense. Other people live in dreams, but not in their own. That's the difference.

- We aren't pigs as you seem to think, but human beings. We create gods and struggle with them, and they bless us.

- You, too, have mysteries of your own. I know that you must have dreams that you don't tell me. I don't want to know them. But I can tell you: live those dreams, play with them, build altars to them. It is not yet the ideal but it points in the right direction. Whether you and I and a few others will renew the world someday remains to be seen. But within ourselves we must renew it each day, otherwise we just aren't serious. Don't forget that!

- Each man had only one genuine vocation — to find the way to himself.

- The world, as it is now, wants to die, wants to perish — and it will.

- You must find your dream, then the way becomes easy. But there is no dream that lasts forever, each dream is followed by another, and one should not cling to any particular one.

- Love does not entreat; or demand. Love must have the strength to become certain within itself. Then it ceases merely to be attracted and begins to attract.

Siddhartha (1922)

- When you throw a rock into the water, it will speed on the fastest course to the bottom of the water. This is how it is when Siddhartha has a goal, a resolution. Siddhartha does nothing, he waits, he thinks, he fasts, but he passes through the things of the world like a rock through water, without doing anything, without stirring; he is drawn, he lets himself fall. His goal attracts him, because he doesn't let anything enter his soul which might oppose the goal. This is what Siddhartha has learned among the Samanas. This is what fools call magic and of which they think it would be effected by means of the daemons. Nothing is effected by daemons, there are no daemons. Everyone can perform magic, everyone can reach his goals, if he is able to think, if he is able to wait, if he is able to fast.

- As translated by Ejvind Haas

- They knew a tremendous number of things — But was it worthwhile knowing all these things if they did not know the one important thing, the only important thing?

- There is, so I believe, in the essence of everything, something that we cannot call learning. There is, my friend, only a knowledge — that is everywhere, that is Atman, that is in me and you and in every creature, and I am beginning to believe that this knowledge has no worse enemy than the man of knowledge, than learning.

- Atman is a term used for Hindu and Buddhist concepts of the soul. Variant translation: I am beginning to believe that this knowledge has no worse enemy than the desire to know learning.

- You are like me; you are different from other people. You are Kamala and no one else, and within you there is a stillness and a sanctuary to which you can retreat at any time and be yourself, just as I can. Few people have that capacity and yet everyone could have it.

- Siddhartha to Kamala

- A true seeker could not accept any teachings, not if he sincerely wished to find something. But he who had found, could give his approval to every path, every goal; nothing separated him from all of the other thousands who lived in eternity, who breathed the Divine.

- Although he had reached a high stage of self-discipline and bore his last wound well, he now felt as if these ordinary people were his brothers. Their vanities, desires, and trivialities no longer seemed absurd to him; they had become understandable, lovable, and even worthy of respect.

- These people were worthy of love and admiration in their blind loyalty, in their blind strength and tenacity. With the exception of one small thing, one tiny little thing, they lacked nothing that the sage and thinker had, and that was the consciousness of the unity of all life.

- Within Siddhartha there slowly grew and ripened the knowledge of what wisdom really was and the goal of his long seeking. It was nothing but a preparation of the soul, a capacity, a secret art of thinking, feeling, and breathing thoughts of unity at every moment of life.

- When Siddhartha listened attentively to this river, to the song of a thousand voices; when he did not listen to the sorrow or laughter, when he did not bind his soul to any one particular voice and absorb it in his Self, but heard them all, the whole, the unity; then the great song of a thousand voices consisted of one word: Om — perfection.

- From that hour Siddhartha ceased to fight against his destiny. There shone in his face the serenity of knowledge, of one who is no longer confronted with conflict of desires, who has found salvation, who is in harmony with the stream of events, with the stream of life, full of sympathy and compassion, surrendering himself to the stream, belonging to the unity of all things.

- Wisdom is not communicable. The wisdom which a wise man tries to communicate always sounds foolish... Knowledge can be communicated, but not wisdom. One can find it, live it, do wonders through it, but one cannot communicate and teach it.

- Everything that is thought and expressed in words is one-sided, only half the truth; it all lacks totality, completeness, unity. When the Illustrious Buddha taught about the world, he had to divide it into Samsara and Nirvana, illusion and truth, into suffering and salvation. One cannot do otherwise, there is no other method for those who teach. But the world itself, being in and around us, is never one-sided. Never is a man or a deed wholly Samsara or wholly Nirvana; never is a man wholly a saint or a sinner. This only seems so because we suffer the illusion that time is something real.

- Listen my friend! I am a sinner and you are a sinner, but someday the sinner will be Brahma again, will someday attain Nirvana, will someday become a Buddha. Now this "someday" is illusion; it is only a comparison. The sinner is not on his way to a Buddha-like state; he is not evolving, although our thinking cannot conceive things otherwise. No, the potential Buddha already exists in the sinner; his future is already there. The potential hidden Buddha must be recognized in him, in you, in everybody. The world, Govinda, is not imperfect or slowly evolving along a path to perfection. No, it is perfect at every moment; every sin already carries grace within it, all small children are potential old men, all sucklings have death within them, all dying people — eternal life. It is not possible for one person to see how far another is on the way; the Buddha exits in robber and the dice player; the robber exists in the Brahmin. During deep meditation it is possible to dispel time, to see simultaneously all the past, present, and future, and then everything is good, everything is perfect, everything is Brahman.

- I had to strive for property and experience nausea and the depths of despair in order to learn not to resist them, in order to learn to love the world, and no longer compare it with some kind of desired imaginary world, some imaginary vision of perfection, but to leave it as it is, to love it and be glad to belong to it. These, Govinda, are some of the thoughts in my mind.

- Words do not express thoughts very well. They always become a little different immediately after they are expressed, a little distorted, a little foolish. And yet it also pleases me and seems right that what is of value and wisdom to one man seems nonsense to another.

- Sometimes quoted in grammatically corrected form as "They always become a little different immediately after they are expressed..." but the apparent editing error here is retained in the published versions of this translation.

- Here is a doctrine at which you will laugh. It seems to me, Govinda, that Love is the most important thing in the world. It may be important to great thinkers to examine the world, to explain and despise it. But I think it is only important to love the world, not to despise it, not for us to hate each other, but to be able to regard the world and ourselves and all beings with love, admiration and respect.

Steppenwolf (1927)

- One day I would be a better hand at the game. One day I would learn how to laugh. Pablo was waiting for me, and Mozart too.

- When two cultures collide is the only time when true suffering exists.

- I sped through heaven and saw god at work. I suffered holy pains. I dropped all my defences and was afraid of nothing in the world. I accepted all things and to all things I gave up my heart.

- As a body everyone is single, as a soul never.

- MAGIC THEATER

ENTRANCE NOT FOR EVERYBODY

I tried to open the door, but the heavy old latch would not stir. The display too was over. It had suddenly ceased, sadly convinced of its uselessness. I took a few steps back, landing deep into the mud, but no more letters came. The display was over. For a long time I stood waiting in the mud, but in vain.

Then, when I had given up and gone back to the alley, a few colored letters were dropped here and there, reflected on the asphalt in front of me. I read:

FOR MADMEN ONLY!

- Haller’s sickness of soul, as I now know, is not the eccentricity of a single individual, but the sickness of the times themselves, the neurosis of that generation to which Haller belongs, a sickness, it seems, that by no means attacks the weak and worthless only but rather those who are strongest in spirit and richest in gifts

- The sacred sense of beyond, of timelessness, of a world which had an eternal value and the substance of which was divine had been given back to me today by this friend of mine who taught me dancing.

- Eternity is a mere moment, just long enough for a joke.

- A mere nothing suffices — and the lightning strikes.

Narcissus and Goldmund (1930)

- It is not our purpose to become each other; it is to recognize each other, to learn to see the other and honor him for what he is: each the other's opposite and complement.

- We fear death, we shudder at life's instability, we grieve to see the flowers wilt again and again, and the leaves fall, and in our hearts we know that we, too, are transitory and will soon disappear. When artists create pictures and thinkers search for laws and formulate thoughts, it is in order to salvage something from the great dance of death, to make something that lasts longer than we do.

- All existence seemed to be based on duality, on contrast. Either one was a man or one was a woman, either a wanderer or sedentary burgher, either a thinking person or a feeling person-no one could breathe in at the same time as he breathed out, be a man as well as a woman, experience freedom as well as order, combine instinct and mind. One always had to pay for one with the loss of the other, and one thing was always just as important and desirable as the other.

- How mysterious this life was, how deep and muddy its waters ran, yet how clear and noble what emerged from them.

- One thing, however, did become clear to him [Goldmund] – why so many perfect works of art did not please him at all, why they were almost hateful and boring to him, in spite of a certain undeniable beauty. Workshops, churches, and palaces were full of these fatal works of art; he had even helped with a few himself. They were deeply disappointing because they aroused the desire for the highest and did not fulfill it. They lacked the most essential thing – mystery. That was what dreams and truly great works of art had in common: mystery.

- If I know what love is, it is because of you.

- Without a mother, one cannot love. Without a mother, one cannot die.

Journey to the East (1932)

- Die Morgenlandfahrt (1932)

- It was my destiny to join in a great experience. Having had the good fortune to belong to the League, I was permitted to be a participant in unique journey. What wonder it had at the time! How radiant and comet-like it seemed, and how quickly it has been forgotten and allowed to fall into disrepute. For this reason, I have decided to attempt a short description of this fabulous journey, a journey the like of which had not been attempted since the days of Hugo and mad Roland.

- He thought for a moment, brought back from his reflections. "It was only possible for me to do it," he said, "because it was necessary. I either had to write the book or be reduced to despair; it was the only means of saving me from nothingness, chaos and suicide. The book was written under this pressure and brought me the expected cure, simply because it was written, irrespective of whether it was good or bad. That was the only thing that counted. And while writing it, there was no need for me to think at all of any other reader but myself, or at the most, here and there another close war comrade, and I certainly never thought then about the survivors, but always about those who fell in the war. While writing it, I was as if delirious or crazy, surrounded by three or four people with mutilated bodies — that is how the book was produced."

The Glass Bead Game (1943)

- For although in a certain sense and for light-minded persons non-existent things can be more easily and irresponsibly represented in words than existing things, for the serious and conscientious historian it is just the reverse. Nothing is harder, yet nothing is more necessary, than to speak of certain things whose existence is neither demonstrable nor probable. The very fact that serious and conscientious men treat them as existing things brings them a step closer to existence and to the possibility of being born.

- Motto of the work written by Hesse, and attributed to an "Albertus Secundus"

- There were entertaining, impassioned, or witty lectures on Goethe, say, in which he would be depicted descending from a post chaise wearing a blue frock-coat to seduce some Strassburg or Wetzlar girl; or on Arabic culture; in all of them a number of fashionable phrases were shaken up like dice in a cup and everyone was delighted if he dimly recognized one or two catchwords.

- The "music of decline" had sounded, as in that wonderful Chinese fable; like a thrumming bass on the organ its reverberations faded slowly out over decades; its throbbing could be heard in the corruption of the schools, periodicals, and universities, in melancholia and insanity among those artists and critics who could still be taken seriously; it raged as untrammeled and amateurish overproduction in all the arts.

- When an orchestra of the Journeyers first publicly performed a suite from the time before Handel completely without crescendi and diminuendi, with the naïveté and chasteness of another age and world, some among the audience are said to have been totally uncomprehending, but others listened with fresh attention and had the impression that they were hearing music for the first time in their lives. In the League's concert hall between Bremgarten and Morbio, one member built a Bach organ as perfectly as Johann Sebastian Bach would have had it built had he had the means and opportunity.

- The young people who now proposed to devote themselves to intellectual studies no longer took the term to mean attending a university and taking a nibble of this or that from the dainties offered by celebrated and loquacious professors who without authority offered them the crumbs of what had once been higher education. Now they had to study just as stringently and methodically as the engineers and technicians of the past, if not more so. They had a steep path to climb, had to purify and strengthen their minds by dint of mathematics and scholastic exercises in Aristotelian philosophy. Moreover, they had to learn to renounce all those benefits which previous generations of scholars had considered worth striving for: rapid and easy money-making, celebrity and public honors, the homage of the newspapers, marriages with daughters of bankers and industrialists, a pampered and luxurious style of life.

- Let us say that the freedom exists, but it is limited to the one unique act of choosing the profession. Afterward all freedom is over. When he begins his studies at the university, the doctor, lawyer, or engineer is forced into an extremely rigid curriculum which ends with a series of examinations. If he passes them, he receives his license and can thereafter pursue his profession in seeming freedom. But in doing so he becomes the slave of base powers; he is dependent on success, on money, on his ambition, his hunger for fame, on whether or not people like him. He must submit to elections, must earn money, must take part in the ruthless competition of castes, families, political parties, newspapers. In return he has the freedom to become successful and well-to-do, and to be hated by the unsuccessful, or vice versa.

- To be capable of everything and do justice to everything, one certainly does not need less spiritual force and èlan and warmth, but more. What you call passion is not spiritual force, but friction between the soul and the outside world. Where passion dominates, that does not signify the presence of greater desire and ambition, but rather the misdirection of these qualities toward an isolated and false goal, with a consequent tension and sultriness in the atmosphere. Those who direct the maximum force of their desires toward the center, toward true being, toward perfection, seem quieter than the passionate souls because the flame of their fervor cannot always be seen.

- "If only there were a dogma to believe in. Everything is contradictary, everything tangential; there are no certainties anywhere. Everything can be interpreted one way and then again intterpreted in the opposite sense. The whole of history can be explained as development and progress and can also be seen as nothing but decadence and meaninglessness. Isn't there any truth? Is there no real and valid doctrine?"

The Master had never heard him speak so fervently. He walked on in silence for a little, then said, "There is truth, my boy. But the doctrine you desire, absolute, perfect dogma that alone provides wisdom, does not exist. Nor should you long for a perfect doctrine, my friend. Rather, you should long for the perfection of yourself. The deity is within you, not in ideas and books. Truth is lived, not taught. Be prepared for conflicts, Joseph Knecht — I can see they have already begun."

- Joseph Knecht had often noticed that many schoolmates his own age, but even more the younger boys, liked him, sought his friendship, and moreover tended to let him dominate them. They asked him for advice, put themselves under his influence. Ever since, this experience had been repeated frequently. It had its pleasant and flattering side; it satisfied ambition and strengthened self-confidence. But it also had another, a dark and terrifying side. For there was something bad and unpalatable about the attitude one took toward these schoolmates so eager for advice, guidance, and an example, about the impulse to despise them for their lack of self-reliance and dignity, and about the occasional secret temptation to make them (at least in thought) into obedient slaves.

- It was lovely, and tempting, to exert power over men and to shine before others, but power also had its perditions and perils. History, after all, consisted of an unbroken succession of rulers, leaders, bosses, and commanders who with extremely rare exceptions had all begun well and ended badly. All of them, at least so they said, had striven for power for the sake of the good; afterward they had become obsessed and numbed by power and loved it for its own sake.

- How alien our country has become from her noblest Province and how unfaithful to that Province's spirit; how far body and soul, ideal and reality have moved apart in our country; how little they know about each other, or want to know.

- It is a pity that you students aren't fully aware of the luxury and abundance in which you live. But I was exactly the same when I was still a student. We study and work, don't waste much time, and think we may rightly call ourselves industrious — but we are scarcely conscious of all we could do, all that we might make of our freedom. Then we suddenly receive a call from the hierarchy, we are needed, are given a teaching assignment, a mission, a post, and from then on move up to a higher one, and unexpectedly find ourselves caught in a network of duties that tightens the more we try to move inside it. All the tasks are in themselves small, but each one has to be carried out at its proper hour, and the day has far more tasks than hours. That is well; one would not want it to be different. But if we ever think, between classroom, archives, secretariat, consulting room, meetings, and official journeys — if we ever think of the freedom we possessed and have lost, the freedom for self-chosen tasks, for unlimited, far-flung studies, we may well feel the greatest yearning for those days, and imagine that if we ever had such freedom again we would fully enjoy its pleasures and potentialities.

- I had tasted the bait and knew that there was nothing more attractive and more subtle on earth than the Game. I had also observed fairly early that this enchanting Game demanded more than naive amateur players, that it took total possession of the man who had succumbed to its magic. And an instinct within me rebelled against my throwing all my energies and interests into this magic forever. Some naive feeling for simplicity, for wholeness and soundness, warned me against the spirit of the Waldzell Vicus Lusorum. I sensed in it a spirit of specialism and virtuosity, certainly highly cultivated, certainly richly elaborated, but nevertheless isolated from humanity and the whole of life — a spirit that had soared too high into haughty solitariness. For years I doubted and probed, until the decision had matured within me and in spite of everything I decided in favor of the Game. I did so because I had within me that urge to seek the supreme fulfillment and serve only the greatest master.

- Ordinarily, when he thought back upon those days, let alone upon his student years and the Bamboo Grove, it had always been as if he were gazing from a cool, dull room out into broad, brightly sunlit landscapes, into the irrevocable past, the paradise of memory. Such recollections had always been, even when they were free of sadness, a vision of things remote and different, separated from the prosaic present by a mysterious festiveness.

- It was as if by becoming a musician and Music Master he had chosen music as one of the ways toward man's highest goal, inner freedom, purity, perfection, and as though ever since making that choice he has done nothing but let himself be more and more permeated, transformed, purified by music — his entire self from his nimble, clever pianist's hands and his vast, well-stocked musician's memory to all the parts and organs of body and soul, to his pulses and breathing, to his sleep and dreaming — so that he was now only a symbol, or rather a manifestation, a personification of music.

- We were picking apart a problem in linguistic history and, as it were, examining close up the peak period of glory in the history of a language; in minutes we had traced the path which had taken it several centuries. And I was powerfully gripped by the vision of transitoriness: the way before our eyes such a complex, ancient, venerable organism, slowly built up over many generations, reaches its highest point, which already contains the germ of decay, and the whole intelligently articulated structure begins to droop, to degenerate, to totter toward its doom. And at the same time the thought abruptly shot through me, with a joyful, startled amazement, that despite the decay and death of that language it had not been lost, that its youth, maturity, and downfall were preserved in our memory, in our knowledge of it and its history, and would survive and could at any time be reconstructed in the symbols and formulas of scholarship as well as in the recondite formulations of the Glass Bead Game. I suddenly realized that in the language, or at any rate in the spirit of the Glass Bead Game, everything actually was all-meaningful, that every symbol and combination of symbols led not hither and yon, not to single examples, experiments, and proofs, but into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world, into primal knowledge. Every transition from major to minor in a sonata, every transformation of a myth or a religious cult, every classical or artistic formulation was, I realized in that flashing moment, if seen with a meditative mind, nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery, where in the alternation between inhaling and exhaling, between heaven and earth, between Yin and Yang, holiness is forever being created.

Quotes about Hermann Hesse

- Few writers have chronicled with such dispassionate lucidity and fearless honesty the progress of the soul through the states of life.

- Dr. Timothy Leary, quoted in a 1969 Panther Books Ltd. edition of Demian (1919)

- In Germany many readers, blandly ignoring the implicit criticism in the novel, tended to see in Hesse's cultural province nothing but a welcome Utopian escape from the harsh postwar realities. More discerning European critics have usually been so preoccupied with the fashionably grave implications that they have neither laughed at its humor nor smiled at its ironies. In part these one-sided readings are understandable, for the humor is often hidden in private jokes of the sort to which Hesse became increasingly partial in his later years. The games begin on the title-page, for the motto attributed to "Albertus Secundus" is actually fictitious. Hesse wrote the motto himself and had it translated into Latin by two former schoolmates, who are cited in Latin abbreviation as the editors: Franz Schall ("noise" or Clangor ) and Feinhals ("slender neck" or Collo fino ). The book is full of this "onomastic comedy" that appealed to Thomas Mann, also a master of the art.

- Theodore Ziolkowski, on The Glass Bead Game (1943), in a Foreword to a 1969 edition of the novel.