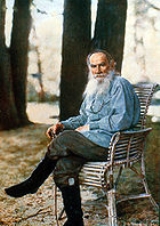

Leo Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevitch Tolstoy [Ле́в Никола́евич Толсто́й] (9 September 1828 – 20 November 1910) was a Russian writer, philosopher and social activist; his name is usually rendered into English as Leo Tolstoy, and sometimes Tolstoi.

Sourced

- The hero of my tale, whom I love with all the power of my soul, whom I have tried to portray in all his beauty, who has been, is, and will be beautiful, is Truth.

- Sevastopol in May 1855 (1855)

- Error is the force that welds men together; truth is communicated to men only by deeds of truth.

- My Religion, Ch. 12 (1885)

- Martin's soul grew glad. He crossed himself put on his spectacles, and began reading the Gospel just where it had opened; and at the top of the page he read: I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat; I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink; I was a stranger, and ye took me in. And at the bottom of the page he read: Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of these my brethren even these least, ye did it unto me (Matt. xxv). And Martin understood that his dream had come true; and that the Saviour had really come to him that day, and he had welcomed him.

- "Where Love Is, God Is" (1885), also translated as "Where Love is, There God is Also" - (full text online)

- Ivan Ilych's life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.

- The Death of Ivan Ilych, Ch. II (1886)

- Ivan Ilych saw that he was dying, and he was in continual despair. In the depth of his heart he knew he was dying, but not only was he not accustomed to the thought, he simply did not and could not grasp it. The syllogism he had learnt from Kiesewetter's Logic: "Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal," had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius — man in the abstract — was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius, not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others.

- The Death of Ivan Ilych, Ch. VI

- A man can live and be healthy without killing animals for food; therefore, if he eats meat, he participates in taking animal life merely for the sake of his appetite. And to act so is immoral.

- Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence (1886)

- I sit on a man's back, choking him, and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am very sorry for him and wish to ease his lot by any means possible, except getting off his back.

- Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence (1886)

- Six feet of land was all that he needed.

- How Much Land Does a Man Need? (1886)

- The happiness of men consists in life. And life is in labor.

- What Is To Be Done? (1886) Chap. XXXVIII, as translated in The Novels and Other Works of Lyof N. Tolstoï (1902) edited by Nathan Haskell Dole, p. 259

- The vocation of every man and woman is to serve other people.

- What Is To Be Done? (1886) Chap. XL, as translated in The Novels and Other Works of Lyof N. Tolstoï (1902) edited by Nathan Haskell Dole, p. 281

- If a man aspires towards a righteous life, his first act of abstinence is from injury to animals.

- The First Step (1892)

- The more is given the less the people will work for themselves, and the less they work the more their poverty will increase.

- Help for the Starving, Pt. III (January 1892)

- God is the infinite ALL. Man is only a finite manifestation of Him.

Or better yet:

God is that infinite All of which man knows himself to be a finite part.

God alone exists truly. Man manifests Him in time, space and matter. The more God's manifestation in man (life) unites with the manifestations (lives) of other beings, the more man exists. This union with the lives of other beings is accomplished through love.

God is not love, but the more there is of love, the more man manifests God, and the more he truly exists...

We acknowledge God only when we are conscious of His manifestation in us. All conclusions and guidelines based on this consciousness should fully satisfy both our desire to know God as such as well as our desire to live a life based on this recognition.- Entry in Tolstoy's Diary (1 November 1910)

- If you want to be happy, be.

- As quoted in Wisdom for the Soul : Five Millennia of Prescriptions for Spiritual Healing (2006) by Larry Chang, p. 352

War and Peace (1865-1869)

- "What's this? Am I falling? My legs are giving way under me," he thought, and fell on his back. He opened his eyes, hoping to see how the struggle of the French soldiers with the artilleryman was ending, and eager to know whether the red-haired gunner artilleryman was killed or not, whether the cannons had been taken or saved. But he saw nothing of all that. Above him there was nothing but the sky — the lofty sky, not clear, but still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds creeping quietly over it.

- Bk. III, ch. 16

- Three days later the little princess was buried, and Prince Andrew went up the steps to where the coffin stood, to give her the farewell kiss. And there in the coffin was the same face, though with closed eyes. "Ah, what have you done to me?" it still seemed to say, and Prince Andrew felt that something gave way in his soul and that he was guilty of a sin he could neither remedy nor forget.

- Bk. IV, ch. 9

- Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly. It is the one thing we are interested in here.

- Book IV, ch. 11

- You will die — and it will all be over. You will die and find out everything — or cease asking.

- Bk. V, ch. 1

- In historical events great men — so-called — are but labels serving to give a name to the event, and like labels they have the least possible connection with the event itself. Every action of theirs, that seems to them an act of their own free will, is in an historical sense not free at all, but in bondage to the whole course of previous history, and predestined from all eternity.

- Bk. IX, ch. 1

- A king is history's slave.

- Bk. IX, ch. 1

- A Frenchman is self-assured because he regards himself personally, both in mind and body, as irresistibly attractive to men and women. An Englishman is self-assured, as being a citizen of the best-organized state in the world, and therefore as an Englishman always knows what he should do and knows that all he does as an Englishman is undoubtedly correct. An Italian is self-assured because he is excitable and easily forgets himself and other people. A Russian is self-assured just because he knows nothing and does not want to know anything, since he does not believe that anything can be known. The German's self-assurance is worst of all, stronger and more repulsive than any other, because he imagines that he knows the truth — science — which he himself has invented but which is for him the absolute truth.

- Bk. IX, ch. 10

- Everything comes in time to him who knows how to wait.

- Bk. X, ch. 16

- The strongest of all warriors are these two — Time and Patience.

- Bk. X, ch. 16

- At the approach of danger there are always two voices that speak with equal force in the heart of man: one very reasonably tells the man to consider the nature of the danger and the means of avoiding it; the other even more reasonable says that it is too painful and harassing to think of the danger, since it is not a man's power to provide for everything and escape from the general march of events; and that it is therefore better to turn aside from the painful subject till it has come, and to think of what is pleasant. In solitude a man generally yields to the first voice; in society to the second.

- Bk. X, ch. 17

- He did not, and could not, understand the meaning of words apart from their context. Every word and action of his was the manifestation of an activity unknown to him, which was his life.

- About Platon Karataev in Bk. XII, ch. 13

- Love hinders death. Love is life. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love. Everything is united by it alone. Love is God, and to die means that I, a particle of love, shall return to the general and eternal source.

- Thoughts of Prince Andrew Bk XIII, Ch. 16

- While imprisoned in the shed Pierre had learned not with his intellect but with his whole being, by life itself, that man is created for happiness, that happiness is within him, in the satisfaction of simple human needs, and that all unhappiness arises not from privation but from superfluity. And now during these last three weeks of the march he had learned still another new, consolatory truth- that nothing in this world is terrible. He had learned that as there is no condition in which man can be happy and entirely free, so there is no condition in which he need be unhappy and lack freedom. He learned that suffering and freedom have their limits and that those limits are very near together....

- Bk. XIV, ch. 12

- To love life is to love God. Harder and more blessed than all else is to love this life in one's sufferings, in undeserved sufferings.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 15

- For us, with the rule of right and wrong given us by Christ, there is nothing for which we have no standard. And there is no greatness where there is not simplicity, goodness, and truth.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 18

- Pure and complete sorrow is as impossible as pure and complete joy.

- Bk. XV, ch. 1

- History is the life of nations and of humanity. To seize and put into words, to describe directly the life of humanity or even of a single nation, appears impossible.

- Modern history, like a deaf man, answers questions no one has asked.

If the purpose of history be to give a description of the movement of humanity and of the peoples, the first question — in the absence of a reply to which all the rest will be incomprehensible — is: what is the power that moves peoples? To this, modern history laboriously replies either that Napoleon was a great genius, or that Louis XIV was very proud, or that certain writers wrote certain books.

All that may be so and mankind is ready to agree with it, but it is not what was asked.- Epilogue II, ch. 1

Anna Karenina (1875–1877)

- Vengeance is mine; I will repay.

- Epigraph

- All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- Pt. I, ch. 1

- Variant translations: Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

All happy families resemble one another; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- He knew she was there by the joy and fear that overwhelmed his heart.

- Pt. I, ch. 9

- He stepped down, trying not to look long at her, as if she were the sun, yet he saw her, like the sun, even without looking.

- Pt. I, ch. 9

- Vronsky, meanwhile, in spite of the complete realization of what he had so long desired, was not perfectly happy. He soon felt that the realization of his desires gave him no more than a grain of sand out of the mountain of happiness he had expected. It showed him the mistake men make in picturing to themselves happiness as the realization of their desires. For a time after joining his life to hers, and putting on civilian dress, he had felt all the delight of freedom in general, of which he had known nothing before, and of freedom in his love — and he was content, but not for long. He was soon aware that there was springing up in his heart a desire for desires — longing. Without conscious intention he began to clutch at every passing caprice, taking it for a desire and an object.

- There is one evident, indubitable manifestation of the Divinity, and that is the laws of right which are made known to the world through Revelation.

- Pt. VII, ch. 19

- One can insult an honest man or an honest woman, but to tell a thief that he is a thief is merely la constation d'un fait [The establishing of a fact.]

- Pt. IV, ch. 4

What Men Live By (1881)

- Go — take the mother's soul, and learn three truths: Learn What dwells in man, What is not given to man, and What men live by. When thou hast learnt these things, thou shalt return to heaven.

- Ch. IV

- I thought: "I am perishing of cold and hunger, and here is a man thinking only of how to clothe himself and his wife, and how to get bread for themselves. He cannot help me. When the man saw me he frowned and became still more terrible, and passed me by on the other side. I despaired, but suddenly I heard him coming back. I looked up, and did not recognize the same man: before, I had seen death in his face; but now he was alive, and I recognized in him the presence of God.

- Then I remembered the first lesson God had set me: "Learn what dwells in man." And I understood that in man dwells Love! I was glad that God had already begun to show me what He had promised, and I smiled for the first time.

- Ch. XI

- The man is making preparations for a year, and does not know that he will die before evening. And I remembered God's second saying, "Learn what is not given to man."

'What dwells in man" I already knew. Now I learnt what is not given him. It is not given to man to know his own needs.- Ch. XI

- When the woman showed her love for the children that were not her own, and wept over them, I saw in her the living God, and understood What men live by.

- Ch. XI

- And the angel's body was bared, and he was clothed in light so that eye could not look on him; and his voice grew louder, as though it came not from him but from heaven above. And the angel said:

I have learnt that all men live not by care for themselves, but by love.

It was not given to the mother to know what her children needed for their life. Nor was it given to the rich man to know what he himself needed. Nor is it given to any man to know whether, when evening comes, he will need boots for his body or slippers for his corpse.

I remained alive when I was a man, not by care of myself, but because love was present in a passer-by, and because he and his wife pitied and loved me. The orphans remained alive, not because of their mother's care, but because there was love in the heart of a woman a stranger to them, who pitied and loved them. And all men live not by the thought they spend on their own welfare, but because love exists in man.

I knew before that God gave life to men and desires that they should live; now I understood more than that.

I understood that God does not wish men to live apart, and therefore he does not reveal to them what each one needs for himself; but he wishes them to live united, and therefore reveals to each of them what is necessary for all.

I have now understood that though it seems to men that they live by care for themselves, in truth it is love alone by which they live. He who has love, is in God, and God is in him, for God is love.- Ch. XII

Confession (1882)

- Quite often a man goes on for years imagining that the religious teaching that had been imparted to him since childhood is still intact, while all the time there is not a trace of it left in him.

- Pt. I, ch. 1

- I cannot recall those years without horror, loathing, and heart-rending pain. I killed people in war, challenged men to duels with the purpose of killing them, and lost at cards; I squandered the fruits of the peasants' toil and then had them executed; I was a fornicator and a cheat. Lying, stealing, promiscuity of every kind, drunkenness, violence, murder — there was not a crime I did not commit... Thus I lived for ten years.

- Pt. I, ch. 2

- Several times I asked myself, "Can it be that I have overlooked something, that there is something which I have failed to understand? Is it not possible that this state of despair is common to everyone?" And I searched for an answer to my questions in every area of knowledge acquired by man. For a long time I carried on my painstaking search; I did not search casually, out of mere curiosity, but painfully, persistently, day and night, like a dying man seeking salvation. I found nothing.

- Pt. I, ch. 5

The Kingdom of God is Within You (1894)

- The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.

- Ch. III

- The only significance of life consists in helping to establish the kingdom of God; and this can be done only by means of the acknowledgment and profession of the truth by each one of us.

- Ch. 12

- Variant translation: The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity by contributing to the establishment of the kingdom of God, which can only be done by the recognition and profession of the truth by every man.

- The Quakers sent me books, from which I learnt how they had, years ago, established beyond doubt the duty for a Christian of fulfilling the command of non-resistance to evil by force, and had exposed the error of the Church's teaching in allowing war and capital punishment.

- Further acquaintance with the labors of the Quakers and their works — with Fox, Penn, and especially the work of Dymond (published in 1827) — showed me not only that the impossibility of reconciling Christianity with force and war had been recognized long, long ago, but that this irreconcilability had been long ago proved so clearly and so indubitably that one could only wonder how this impossible reconciliation of Christian teaching with the use of force, which has been, and is still, preached in the churches, could have been maintained in spite of it.

- William Lloyd Garrison took part in a discussion on the means of suppressing war in the Society for the Establishment of Peace among Men, which existed in 1838 in America. He came to the conclusion that the establishment of universal peace can only be founded on the open profession of the doctrine of non-resistance to evil by violence (Matt. v. 39), in its full significance, as understood by the Quakers, with whom Garrison happened to be on friendly relations. Having come to this conclusion, Garrison thereupon composed and laid before the society a declaration, which was signed at the time — in 1838 — by many members.

- The error arises from the learned jurists deceiving themselves and others, by asserting that government is not what it really is, one set of men banded together to oppress another set of men, but, as shown by science, is the representation of the citizens in their collective capacity.

- Variant: Government is an association of men who do violence to the rest of us.

- Armies are necessary, before all things, for the defense of governments from their own oppressed and enslaved subjects.

What is Art? (1896)

- Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which men have risen.

- Ch. 8

- The assertion that art may be good art and at the same time incomprehensible to a great number of people is extremely unjust, and its consequences are ruinous to art itself...it is the same as saying some kind of food is good but most people can't eat it.

- People understand the meaning of eating lies in the nourishment of the body only when they cease to consider that the object of that activity is pleasure. ...People understand the meaning of art only when they cease to consider that the aim of that activity is beauty, i.e., pleasure.

- In spite the mountains of books written about art, no precise definition of art has been constructed. And the reason for this is that the conception of art has been based on the conception of beauty.

- In order to correctly define art, it is necessary, first of all, to cease to consider it as a means to pleasure and consider it as one of the conditions of human life. ...Reflecting on it in this way, we cannot fail to observe that art is one of the means of affective communication between people.

- By words one transmits thoughts to another, by means of art, one transmits feelings.

- To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, then by means of movements, lines, colors, sounds, or forms expressed through words, so to convey this so that others may experience the same feeling — this is the activity of art.

- Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one consciously, by means of certain external symbols, conveys to others the feelings one has experienced, whereby people so infected by these feelings, also experience them.

- Art is not, as the metaphysicians say, the manifestation of some mysterious Idea of beauty or God; it is not, as the aesthetical physiologists say, [play or] a game in which one releases surplus energy, ...not the production of pleasing objects, and is above all, not pleasure itself, but it is the means of union among mankind, joining them in the same feelings, and necessary for the life and progress toward the good of the individual and of humanity.

- The activity of art is... as important as the activity of language itself, and as universal.

- Some teachers of mankind — as Plato... the first Christians, the orthodox Muslims, and the Buddhists — have gone so far as to repudiate art. ...[They consider it] so highly dangerous in its power to infect people against their wills, that mankind will lose far less by banishing all art than by tolerating each and every art. ...such people were wrong in repudiating all art, for they denied that which cannot be denied — one of the indispensable means of communication, without which mankind could not exist. ...Now there is only fear, lest we should be deprived of any pleasures art can afford, so any type of art is patronized. And I think the last error is much grosser than the first and that its consequences are far more harmful.

- The appreciation of the merits of art (of the emotions it conveys) depends upon an understanding of the meaning of life, what is seen as good and evil. Good and evil are defined by religions.

- Humanity unceasingly strives forward from a lower, more partial and obscure understanding of life to one more general and more lucid. And in this, as in every movement, there are leaders — those who have understood the meaning of life more clearly than others — and of those advanced men there is always one who has in his words and life, manifested this meaning more clearly, accessibly, and strongly than others. This man's expression ... with those superstitions, traditions, and ceremonies which usually form around the memory of such a man, is what is called a religion. Religions are the exponents of the highest comprehension of life ... within a given age in a given society ... a basis for evaluating human sentiments. If feelings bring people nearer to the religion's ideal ... they are good, if these estrange them from it, and oppose it, they are bad.

- The Christianity of the first centuries recognized as productions of good art, only legends, lives of saints, sermons, prayers, and hymn-singing evoking love of Christ, emotion at his life, desire to follow his example, renunciation of worldly life, humility, and the love of others; all productions transmitting feelings of personal enjoyment they considered to be bad, and therefore rejected ... This was so among the Christians of the first centuries who accepted Christ teachings, if not quite in its true form, at least not yet in the perverted, paganized form in which it was accepted subsequently.

But besides this Christianity, from the time of the wholesale conversion of whole nations by order of the authorities, as in the days of Constantine, Charlemagne and Vladimir, there appeared another , a Church Christianity, which was nearer to paganism than to Christ's teaching. And this Church Christianity ... did not acknowledge the fundamental and essential positions of true Christianity — the direct relationship of each individual to the Father, the consequent brotherhood and equality of all people, and the substitution of humility and love in place of every kind of violence — but, on the contrary, having founded a heavenly hierarchy similar to the pagan mythology, and having introduced the worship of Christ, of the Virgin, of angels, of apostles, of saints, and of martyrs, but not only of these divinities themselves but of their images, it made blind faith in its ordinances an essential point of its teachings.

However foreign this teaching may have been to true Christianity, however degraded, not only in comparison with true Christianity, but even with the life-conception of the Romans such as Julian and others, it was for all that, to the barbarians who accepted it, a higher doctrine than their former adoration of gods, heroes, and good and bad spirits. And therefore this teaching was a religion to them, and on the basis of that religion the art of the time was assessed. And art transmitting pious adoration of the Virgin, Jesus, the saints, and the angels, a blind faith in and submission to the Church, fear of torments and hope of blessedness in a life beyond the grave, was considered good; all art opposed to this was considered bad.

- In the upper, rich, more educated classes of European society doubt arose as to the truth of that understanding of life which was expressed by Church Christianity. When, after the Crusades and the maximum development of papal power and its abuses, people of the rich classes became acquainted with the wisdom of the classics and saw, on the one hand, the reasonable lucidity of the teachings of the ancient sages, and on the other hand, the incompatibility of the Church doctrine with the teaching of Christ, they found it impossible to continue to believe the Church teaching.

- No longer able to believe in the Church religion, whose falsehood they had detected, and incapable of accepting true Christian teaching, which denounced their whole manner of life, these rich and powerful people, stranded without any religious conception of life, involuntarily returned to that pagan view of things which places life's meaning in personal enjoyment. And then among the upper classes what is called the "Renaissance of science and art" took place, which was really not only a denial of every religion, but also an assertion that religion was unnecessary.

- So the majority of the highest classes of that age, even the popes and ecclesiastics, really believed in nothing at all. They did not believe in the Church doctrine, for they saw its insolvency; but neither could they follow Francis of Assisi, Kelchitsky, and most of the sectarians in acknowledging the moral, social teaching of Christ, for that undermined their social position. And so these people remained without any religious view of life. And, having none, they could have no standard with which to estimate what was good and what was bad art, but that of personal enjoyment.

- Having acknowledged the measure of the good to be pleasure, i.e., beauty, the European upper classes went back in their comprehension of art to the gross conception of the primitive Greeks which Plato had already condemned. And with this understanding of life, a theory of art was formulated.

- The partisans of aesthetic theory denied that it was their own invention, and professed that it existed in the nature of things and even that it was recognized by the ancient Greeks. But... among the ancient Greeks, due to their low grade (compared to the Christian) moral ideal, their conception of the good was not yet sharply distinguished from their conception of the beautiful. That highest conception of goodness (not identical with beauty and for the most part, contrasting with it) discerned by the Jews even in the time of Isaiah and fully expressed by Christianity, was unknown to the Greeks. It is true that the Greek's foremost thinkers — Socrates, Plato, Aristotle — felt that goodness may not coincide with beauty. ...But notwithstanding all this, they could not quite dismiss the notion that beauty and goodness coincide. And consequently in the language of that period a compound word (καλο-κάγαθια, beauty-goodness) came into use to express that notion. Evidently the Greek sages began to draw close to the perception of goodness which is expressed in Buddhism and in Christianity, but they got entangled in defining the relationship between goodness and beauty. And it was just this confusion of ideas that those Europeans of a later age ... tried to elevate into law. ... On this misunderstanding the new science of aesthetics was built.

- After Plotinus, says Schassler, fifteen centuries passed without the slightest scientific interest for the world of beauty and art. ...In reality, nothing of the kind happened. The science of aesthetics ... neither did nor could vanish, because it never existed. ... the Greeks were so little developed that goodness and beauty seemed to coincide. On that obsolete Greek view of life the science of aesthetics was invented by men of the eighteenth century, and especially shaped and mounted in Baumgarten's theory. The Greeks (as anyone may read in Bénard's book on Aristotle and Walter's work on Plato) never had a science of aesthetics.

- Aesthetic theories arose one hundred fifty years ago among the wealthy classes of the Christian European world. ...And notwithstanding its obvious insolidity, nobody else's theory so pleased the cultured crowd or was accepted so readily and with such absence of criticism. It so suited the people of the upper classes that to this day, notwithstanding its entirely fantastic character and the arbitrary nature of its assertions, it is repeated by the educated and uneducated as though it were something indubitable and self-evident.

- Such ... was the theory (an outgrowth of Malthusian) of the selection and struggle for existence as the basis of human progress. Such again, is Marx's theory, with regard to the gradual destruction of small private production by large capitalistic production... as an inevitable decree of fate. However unfounded such theories are, however contrary to all that is known and confessed by humanity, and however obviously immoral these may be, they are accepted with credulity, pass uncriticized, and are preached ... To this class belongs this astonishing theory of the Baungarten trinity — Goodness, Beauty and Truth — according to which it appears that the very best that can be done by the art of nations after 1900 years of Christian teaching is to choose as the ideal of their life that which was held by a small, semi-savage, slaveholding people who lived 2000 years ago, who imitated the nude human body extremely well, and erected buildings pleasing to the eye. Educated people write long, nebulous treatises on beauty as a member of the aesthetic trinity of beauty, truth, and goodness... and they all think that by pronouncing these sacrosanct words, they speak of something quite definite and solid... on which they can base their opinions. ... only for the purpose of justifying the false importance we attribute to an art that conveys every feeling, provided those feelings give us pleasure.

- The good is the everlasting, the pinnacle of our life. ... life is striving towards the good, toward God. The good is the most basic idea ... an idea not definable by reason ... yet is the postulate from which all else follows. But the beautiful ... is just that which is pleasing. The idea of beauty is not an alignment to the good, but is its opposite, because for most part, the good aids in our victory over our predilections, while beauty is the motive of our predilections. The more we succumb to beauty, the further we are displaced from the good. ...the usual response is that there exists a moral and spiritual beauty ... we mean simply the good. Spiritual beauty or the good, generally not only does not coincide with the typical meaning of beauty, it is its opposite.

- Truth is ... one approach to the attainment of the good, but in and of itself, it is neither the good nor the beautiful ... Socrates, Pascal, and others regarded knowledge of the truth with regard to purposeless objects as incongruous with the good ... [by] exposing deception, truth destroys illusion, which is the principle attribute of beauty.

- And so the arbitrary union of three incommensurate, mutually disconnected concepts became the basis of a bewildering theory... [by which] one of the lowest renderings of art, art for mere pleasure — against which all of the master teachers warned — was idealized as the ultimate in art.

- I know that most men — not only those considered clever, but even those who are very clever and capable of understanding most difficult scientific, mathematical, or philosophic, problems — can seldom discern even the simplest and most obvious truth if it be such as obliges them to admit the falsity of conclusions they have formed, perhaps with much difficulty — conclusions of which they are proud, which they have taught to others, and on which they have built their lives.

- Opening to Ch 14. Translation from: What Is Art and Essays on Art (Oxford University Press, 1930, trans. Aylmer Maude)

- Variant: I know that most men, including those at ease with problems of the greatest complexity, can seldom accept even the simplest and most obvious truth if it be such as would oblige them to admit the falsity of conclusions which they have delighted in explaining to colleagues, which they have proudly taught to others, and which they have woven, thread by thread, into the fabric of their lives.

- As quoted by physicist Joseph Ford in Chaotic Dynamics and Fractals (1985) edited by Michael Fielding Barnsley and Stephen G. Demko

A Letter to a Hindu (1908)

- Full text online

- The oppression of a majority by a minority, and the demoralization inevitably resulting from it, is a phenomenon that has always occupied me and has done so most particularly of late.

- I

- The reason for the astonishing fact that a majority of working people submit to a handful of idlers who control their labour and their very lives is always and everywhere the same — whether the oppressors and oppressed are of one race or whether, as in India and elsewhere, the oppressors are of a different nation. This phenomenon seems particularly strange in India, for there more than two hundred million people, highly gifted both physically and mentally, find themselves in the power of a small group of people quite alien to them in thought, and immeasurably inferior to them in religious morality. ... the reason lies in the lack of a reasonable religious teaching which, by explaining the meaning of life would supply a supreme law for the guidance of conduct, and would replace the more than dubious precepts of pseudoreligion and pseudoscience and the immoral conclusions deduced from them, commonly called "civilization."

- I

- Amid this life based on coercion, one and the same thought constantly emerged among different nations, namely, that in every individual a spiritual element is manifested that gives life to all that exists, and that this spiritual element strives to unite with everything of a like nature to itself, and attains this aim through love.

- II

- The recognition that love represents the highest morality was nowhere denied or contradicted, but this truth was so interwoven everywhere with all kinds of falsehoods which distorted it, that finally nothing of it remained but words. It was taught that this highest morality was only applicable to private life — for home use, as it were — but that in public life all forms of violence — such as imprisonment, executions, and wars — might be used for the protection of the majority against a minority of evildoers, though such means were diametrically opposed to any vestige of love.

- III

- People continued — regardless of all that leads man forward — to try to unite the incompatibles : the virtue of love, and what is opposed to love, namely, the restraining of evil by violence. And such a teaching, despite its inner contradiction, was so firmly established that the very people who recognize love as a virtue accept as lawful at the same time an order of life based on violence and allowing men not merely to torture but even to kill one another.

- III

- In former times the chief method of justifying the use of violence and thereby infringing the law of love was by claiming a divine right for the rulers: the Tsars, Sultans, Rajahs, Shahs, and other heads of states. But the longer humanity lived the weaker grew the belief in this peculiar, God-given right of the ruler. That belief withered in the same way and almost simultaneously in the Christian and the Brahman world, as well as in Buddhist and Confucian spheres, and in recent times it has so faded away as to prevail no longer against man's reasonable understanding and the true religious feeling. People saw more and more clearly, and now the majority see quite clearly, the senselessness and immorality of subordinating their wills to those of other people just like themselves, when they are bidden to do what is contrary not only to their interests but also to their moral sense.

- III

- Unfortunately not only were the rulers, who were considered supernatural beings, benefited by having the peoples in subjection, but as a result of the belief in, and during the rule of, these pseudodivine beings, ever larger and larger circles of people grouped and established themselves around them, and under an appearance of governing took advantage of the people. And when the old deception of a supernatural and God-appointed authority had dwindled away these men were only concerned to devise a new one which like its predecessor should make it possible to hold the people in bondage to a limited number of rulers.

- III

- These new justifications are termed "scientific". But by the term "scientific" is understood just what was formerly understood by the term "religious": just as formerly everything called "religious" was held to be unquestionable simply because it was called religious, so now all that is called "scientific" is held to be unquestionable. In the present case the obsolete religious justification of violence which consisted in the recognition of the supernatural personality of the God-ordained ruler ("there is no power but of God") has been superseded by the "scientific" justification which puts forward, first, the assertion that because the coercion of man by man has existed in all ages, it follows that such coercion must continue to exist. This assertion that people should continue to live as they have done throughout past ages rather than as their reason and conscience indicate, is what "science" calls "the historic law". A further "scientific" justification lies in the statement that as among plants and wild beasts there is a constant struggle for existence which always results in the survival of the fittest, a similar struggle should be carried on among humanbeings, that is, who are gifted with intelligence and love; faculties lacking in the creatures subject to the struggle for existence and survival of the fittest. Such is the second "scientific" justification. The third, most important, and unfortunately most widespread justification is, at bottom, the age-old religious one just a little altered: that in public life the suppression of some for the protection of the majority cannot be avoided — so that coercion is unavoidable however desirable reliance on love alone might be in human intercourse. The only difference in this justification by pseudo-science consists in the fact that, to the question why such and such people and not others have the right to decide against whom violence may and must be used, pseudo-science now gives a different reply to that given by religion — which declared that the right to decide was valid because it was pronounced by persons possessed of divine power. "Science" says that these decisions represent the will of the people, which under a constitutional form of government is supposed to find expression in all the decisions and actions of those who are at the helm at the moment. Such are the scientific justifications of the principle of coercion. They are not merely weak but absolutely invalid, yet they are so much needed by those who occupy privileged positions that they believe in them as blindly as they formerly believed in the immaculate conception, and propagate them just as confidently. And the unfortunate majority of men bound to toil is so dazzled by the pomp with which these "scientific truths" are presented, that under this new influence it accepts these scientific stupidities for holy truth, just as it formerly accepted the pseudo-religious justifications; and it continues to submit to the present holders of power who are just as hard-hearted but rather more numerous than before.

- IV

- A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred millions. Tell this to a man free from superstition and he will fail to grasp what these words mean. What does it mean that thirty thousand men, not athletes but rather weak and ordinary people, have subdued two hundred million vigorous, clever, capable, and freedom-loving people? Do not the figures make it clear that it is not the English who have enslaved the Indians, but the Indians who have enslaved themselves?

- V

- When the Indians complain that the English have enslaved them it is as if drunkards complained that the spirit-dealers who have settled among them have enslaved them. You tell them that they might give up drinking, but they reply that they are so accustomed to it that they cannot abstain, and that they must have alcohol to keep up their energy. Is it not the same thing with the millions of people who submit to thousands or even to hundreds, of others — of their own or other nations? If the people of India are enslaved by violence it is only because they themselves live and have lived by violence, and do not recognize the eternal law of love inherent in humanity.

- V

- As soon as men live entirely in accord with the law of love natural to their hearts and now revealed to them, which excludes all resistance by violence, and therefore hold aloof from all participation in violence — as soon as this happens, not only will hundreds be unable to enslave millions, but not even millions will be able to enslave a single individual.

- V

- Do not resist the evil-doer and take no part in doing so, either in the violent deeds of the administration, in the law courts, the collection of taxes, or above all in soldiering, and no one in the world will be able to enslave you.

- V

- What is now happening to the people of the East as of the West is like what happens to every individual when he passes from childhood to adolescence and from youth to manhood. He loses what had hitherto guided his life and lives without direction, not having found a new standard suitable to his age, and so he invents all sorts of occupations, cares, distractions, and stupefactions to divert his attention from the misery and senselessness of his life. Such a condition may last a long time.

- VI

- When an individual passes from one period of life to another a time comes when he cannot go on in senseless activity and excitement as before, but has to understand that although he has out-grown what before used to direct him, this does not mean that he must live without any reasonable guidance, but rather that he must formulate for himself an understanding of life corresponding to his age, and having elucidated it must be guided by it. And in the same way a similar time must come in the growth and development of humanity.

- VI

- The inherent contradiction of human life has now reached an extreme degree of tension: on the one side there is the consciousness of the beneficence of the law of love, and on the other the existing order of life which has for centuries occasioned an empty, anxious, restless, and troubled mode of life, conflicting as it does with the law of love and built on the use of violence. This contradiction must be faced, and the solution will evidently not be favourable to the outlived law of violence, but to the truth which has dwelt in the hearts of men from remote antiquity: the truth that the law of love is in accord with the nature of man. But men can only recognize this truth to its full extent when they have completely freed themselves from all religious and scientific superstitions and from all the consequent misrepresentations and sophistical distortions by which its recognition has been hindered for centuries.

- VI

- In order that men should embrace the truth — not in the vague way they did in childhood, nor in the one-sided and perverted way presented to them by their religious and scientific teachers, but embrace it as their highest law the complete liberation of this truth from all and every superstition (both pseudo-religious and pseudo-scientific) by which it is still obscured is essential: not a partial, timid attempt, reckoning with traditions sanctified by age and with the habits of the people — not such as was effected in the religious sphere by Guru Nanak, the founder of the sect of the Sikhs, and in the Christian world by Luther, and by similar reformers in other religions — but a fundamental cleansing of religious consciousness from all ancient religious and modern scientific superstitions.

- VI

- If only people freed themselves from their beliefs in all kinds of Ormuzds, Brahmas, Sabbaoths, and their incarnation as Krishnas and Christs, from beliefs in Paradises and Hells, in reincarnations and resurrections, from belief in the interference of the Gods in the external affairs of the universe, and above all, if they freed themselves from belief in the infallibility of all the various Vedas, Bibles, Gospels, Tripitakas, Korans, and the like, and also freed themselves from blind belief in a variety of scientific teachings about infinitely small atoms and molecules and in all the infinitely great and infinitely remote worlds, their movements and origin, as well as from faith in the infallibility of the scientific law to which humanity is at present subjected: the historic law, the economic laws, the law of struggle and survival, and so on, — if people only freed themselves from this terrible accumulation of futile exercises of our lower capacities of mind and memory called the "Sciences", and from the innumerable divisions of all sorts of histories, anthropologies, homiletics, bacteriologics, jurisprudences, cosmographies, strategies — their name is legion — and freed themselves from all this harmful, stupefying ballast — the simple law of love, natural to man, accessible to all and solving all questions and perplexities, would of itself become clear and obligatory.

- VI

- In the spiritual realm nothing is indifferent: what is not useful is harmful.

- VII

- What are wanted for the Indian as for the Englishman, the Frenchman, the German, and the Russian, are not Constitutions and Revolutions, nor all sorts of Conferences and Congresses, nor the many ingenious devices for submarine navigation and aerial navigation, nor powerful explosives, nor all sorts of conveniences to add to the enjoyment of the rich, ruling classes; nor new schools and universities with innumerable faculties of science, nor an augmentation of papers and books, nor gramophones and cinematographs, nor those childish and for the most part corrupt stupidities termed art — but one thing only is needful: the knowledge of the simple and clear truth which finds place in every soul that is not stupefied by religious and scientific superstitions — the truth that for our life one law is valid — the law of love, which brings the highest happiness to every individual as well as to all mankind. Free your minds from those overgrown, mountainous imbecilities which hinder your recognition of it, and at once the truth will emerge from amid the pseudo-religious nonsense that has been smothering it: the indubitable, eternal truth inherent in man, which is one and the same in all the great religions of the world. It will in due time emerge and make its way to general recognition, and the nonsense that has obscured it will disappear of itself, and with it will go the evil from which humanity now suffers.

Quotes about Tolstoy

- I fear Tolstoy's death. His death would leave a large empty space in my life. First, I have loved no man the way I have loved him. I am not a believer, but of all beliefs I consider his the closest to mine and most suitable for me. Second, when literature has a Tolstoy, it is easy and gratifying to be a writer. Even if you are aware that you have never accomplished anything, you don't feel so bad, because Tolstoy accomplishes enough for everyone. His activities provide justification for the hopes and aspirations that are usually placed on literature. Third, Tolstoy stands firm, his authority is enormous, and as long as he is alive bad taste in literature, all vulgarity in its brazen-faced or lachrymose varieties, all bristly and resentful vanity will remain far in the background. His moral authority alone is enough to maintain what we think of as literary trends and schools at a certain minimal level. If not for him, literature would be a flock without a shepherd or an unfathomable jumble.

- Anton Chekhov in letter to M.O. Menshikov. (28 January 1900)

- The truth is that Tolstoy, with his immense genius, with his colossal faith, with his vast fearlessness and vast knowledge of life, is deficient in one faculty and one faculty alone. He is not a mystic; and therefore he has a tendency to go mad. Men talk of the extravagances and frenzies that have been produced by mysticism; they are a mere drop in the bucket. In the main, and from the beginning of time, mysticism has kept men sane. The thing that has driven them mad was logic. ...The only thing that has kept the race of men from the mad extremes of the convent and the pirate-galley, the night-club and the lethal chamber, has been mysticism — the belief that logic is misleading, and that things are not what they seem.

- G. K. Chesterton, in Tolstoy (1903)

- People try so hard to believe in leaders now, pitifully hard. But we no sooner get a popular reformer or politician or soldier or writer or philosopher — a Roosevelt, a Tolstoy, a Wood, a Shaw, a Nietzsche, than the cross-currents of criticism wash him away. My Lord, no man can stand prominence these days. It's the surest path to obscurity.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald in This Side of Paradise (1920)

- Tolstoy's life has been devoted to replacing the method of violence for removing tyranny or securing reform by the method of nonresistance to evil. He would meet hatred expressed in violence by love expressed in selfsuffering. He admits of no exception to whittle down this great and divine law of love. He applies it to all the problems that trouble mankind.

- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (19 November 1909), in his Introduction to the publication of Tolstoy's A Letter to a Hindu (1909)

- I started out very quiet and I beat Mr. Turgenev. Then I trained hard and I beat Mr. de Maupassant. I’ve fought two draws with Mr. Stendhal, and I think I had an edge in the last one. But nobody’s going to get me in any ring with Mr. Tolstoy unless I’m crazy or I keep getting better.

- Ernest Hemingway in The New Yorker (13 May 1950)

- My first reading of Tolstoy affected me as a revelation from heaven, as the trumpet of the judgment. What he made me feel was not the desire to imitate, but the conviction that imitation was futile.

- Ellen Glasgow The Woman Within (Written in 1944; published in 1954)

- It has been said that a careful reading of Anna Karenina, if it teaches you nothing else, will teach you how to make strawberry jam.

- Julian Mitchell, Radio Times, (30 October 1976)

- Even beyond their deaths, the two novelists stand in contrariety. Tolstoy, the foremost heir to the traditions of the epic; Dostoevsky, one of the major dramatic tempers after Shakespeare; Tolstoy, the mind intoxicated with reason and fact; Dostoevsky, the condemner of rationalism, the great lover of paradox; Tolstoy, the poet of the land, of the rural setting and pastoral mood; Dostoevsky, the arch-citizen, the master-builder of the modern metropolis in the province of language; Tolstoy, thirsting for the truth, destroying himself and those about him in excessive pursuit of it; Dostoevsky, rather against the truth than against Christ, suspicious of total understanding and on the side of mystery; Tolstoy, "keeping at all times," in Coleridge's phrase, "in the high road of life"; Dostoevsky, advancing into the labyrinth of the unnatural, into the cellarage and morass of the soul; Tolstoy, like a colossus bestriding the palpable earth, evoking the realness, the tangibility, the sensible entirety of concrete experience; Dostoevsky, always on the verge of the hallucinatory, of the spectral, always vulnerable to daemonic intrusions into what might prove, in the end, to have been merely a tissue of dreams; Tolstoy, the embodiment of health and Olympian vitality; Dostoevsky, the sum of energies charged with illness and possession.

- George Steiner in Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old Criticism (1959)

- It is to Tolstoy whom Mahatma Gandhi gave credit for his own first understanding of nonviolent resistance to oppression, and there is an unbroken lineage from Tolstoy to Gandhi to Martin Luther King.

- "Brief biography" at Masterpiece Theatre (PBS)

- He was a revolutionary in his thinking and later in life he was an activist and reformer; he was best known as Russia's greatest moral authority, and his teachings on civil disobedience have inspired Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and countless others. He was, and still is, an author to be reckoned with.

- Brief biography at Oprah's Book Club