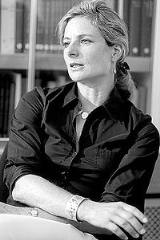

Lisa Randall

Lisa Randall is a leading theoretical physicist and expert on particle physics, string theory and cosmology. She works on several of the competing models of string theory in the quest to explain the fabric of reality, and was the first tenured woman in the Princeton University physics department and the first tenured woman theoretical physicist at MIT and Harvard University.

Warped Passages: Unraveling the Universe's Hidden Dimensions (2005)

- The universe has its secrets. Extra dimensions of space might be one of them. If so, the universe has been hiding those dimensions, protecting them, keeping them coyly under wraps. From a casual glance, you would never suspect a thing.

- Introduction

- Physics has entered a remarkable era. Ideas that were once the realm of science fiction are now entering our theoretical — and maybe even experimental — grasp. Brand-new theoretical discoveries about extra dimensions have irreversibly changed how particle physicists, astrophysicists, and cosmologists now think about the world. The sheer number and pace of discoveries tells us that we've most likely only scratched the surface of the wondrous possibilities that lie in store. Ideas have taken on a life of their own.

- Ch. 24

- We certainly don't yet know all the answers. But the universe is about to be pried open.

- Ch. 25

- Secrets of the cosmos will begin to unravel. I, for one, can't wait.

- Ch. 25

The Discover Interview: Lisa Randall (July 2006)

- When I was in school I liked math because all the problems had answers. Everything else seemed very subjective.

- Sometimes I have a sense of what I'm seeing being a small fraction of what's there. Not always there, but probably more often than I realize. Something will come up, and I'll realize I'm thinking about the world a little differently than my friends.

- In the history of physics, every time we've looked beyond the scales and energies we were familiar with, we've found things that we wouldn't have thought were there. You look inside the atom and eventually you discover quarks. Who would have thought that? It's hubris to think that the way we see things is everything there is.

- If we don't do it now, we'll probably never do it. We've built up the technology; we're at a point where if we don't continue, we'll lose that expertise, and we'll have to start all over again. True, it's expensive, but at the end of the day I believe it will be worth it. It makes a difference in terms of who we are, what we think, how we view the world. These are the kinds of things that get people excited about science, so you have a more educated public.

- Science is not religion. We're not going to be able to answer the "why" questions. But when you put together all of what we know about the universe, it fits together amazingly well.

- Religion asks questions about morals, whereas science just asks questions about the natural world. But when people try to use religion to address the natural world, science pushes back on it, and religion has to accommodate the results. Beliefs can be permanent, but beliefs can also be flexible. Personally, if I find out my belief is wrong, I change my mind. I think that's a good way to live.

- Faith just doesn't have anything to do with what I'm doing as a scientist. It's nice if you can believe in God, because then you see more of a purpose in things. Even if you don't, though, it doesn't mean that there's no purpose. It doesn't mean that there's no goodness. I think that there's a virtue in being good in and of itself. I think that one can work with the world we have.

- I think it's a problem that people are considered immoral if they're not religious. That's just not true. This might earn me some enemies, but in some ways they may be even more moral. If you do something for a religious reason, you do it because you'll be rewarded in an afterlife or in this world. That's not quite as good as something you do for purely generous reasons.